For 15 years, a six-storey concrete gravestone to the late 1980s Toronto office tower boom sat in the heart of downtown. Affectionately nicknamed "The Stump," the unfinished structural core of the first Bay-Adelaide Centre, was a constant reminder that building skyscrapers is a risky business.

The story of the grey, apocalyptic landmark, which marked the location of a massive underground parking garage and took a decade and a half to finally destroy, is one of deal-making, powerful lobbying and awful timing.

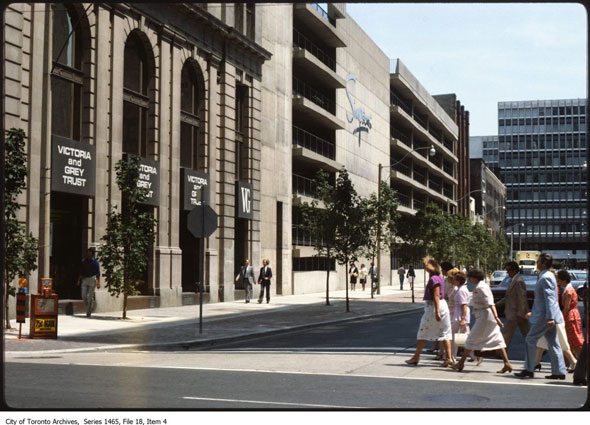

As had been the case with Scotia Plaza a few years earlier, the original version of the Bay-Adelaide Centre was controversial from the outset. The Hudson's Bay Company, the new owner of Simpson's department stores, had, through a series of deals, acquired a large parcel of land south of Queen between Yonge, Bay, and Adelaide.

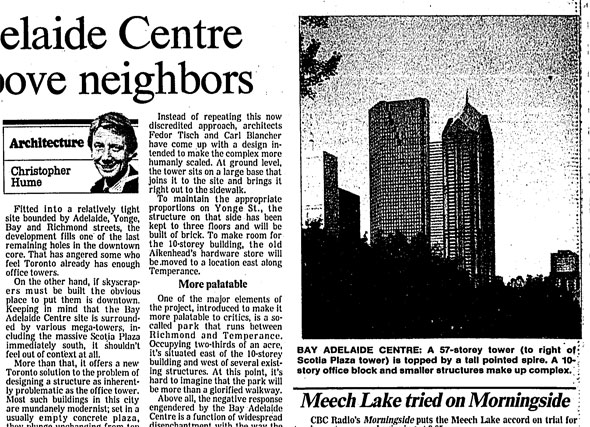

It was here, on the south side of Temperance Street, that HBC and Trizec Equities, the retailer's development partner, planned to build a 57-storey tower with a distinctive pitched roof and spire. The rent from its 158,000 square metres of office space would provide the all-important income. A smaller office tower, roughly 10 to 12-storeys, was planned for the Yonge Street side of the block.

The height of the main tower, which was to be slightly smaller than Scotia Plaza, was made possible by a controversial council decision on the eve of a civic election in October 1988. Essentially, the city cut a deal with the developers that allowed the density of the three separate HBC sites to be added together, creating a "superblock."

In exchange for not demolishing the historic Simpson's store, supplying the space and money for a half-acre park, and land for 561 units of assisted housing, the city allowed an additional 31,400 square metres of space. Toronto Star writer David Lewis Stein called the culture of deal-making "everything that is wrong with the last city council."

The city employed similar tactics during the development of Scotia Plaza in 1984. Then, an agreement reached under Mayor Art Eggleton traded additional height for 200 units of assisted housing and protection for the original Bank of Nova Scotia building. A disgruntled TD Bank waged public war on the project, printing several attack ads in an attempt to keep the angular bank building off its doorstep.

There was more controversy during the tower's development when it was revealed non-profit housing issues group Downtown Action, which had long opposed the tower and counted Metro councillor Jack Layton among its ranks, had agreed to go silent for a $2 million donation to a housing co-operative from the developers. The the city's land use committee found the group "misused" the system.

Construction

began on the first Bay-Adelaide Centre in 1989. A large pit was

excavated on the south side of Temperance, into which a six-storey

parking garage and the structural foundation for the tower was built.

With the discontent over the approval process abating - an independent

review ordered by the new council found the deal to be satisfactory -

critics began to publicly applaud the design.

Construction

began on the first Bay-Adelaide Centre in 1989. A large pit was

excavated on the south side of Temperance, into which a six-storey

parking garage and the structural foundation for the tower was built.

With the discontent over the approval process abating - an independent

review ordered by the new council found the deal to be satisfactory -

critics began to publicly applaud the design.Christopher Hume from the Star predicted the towers would become "instant landmarks." The brown granite and glass exterior with its pointed roof, the product of an international design competition, would be welcome relief from other new downtown buildings, which he called "boxes of boredom." In the same paper, writer Alastair Dow predicted high interest rates and the slow economy would make it hard to fill all that office space.

There had been warning signs years earlier that supply was outstripping demand. In 1986, Joe Barnicke, the president of one of the city's largest leasing firms, was concerned there wouldn't be enough demand for all that space. The vacancy rate was 13% that year without Scotia Plaza, BCE Place (now Brookfield Place,) and the Bay-Adelaide Centre, the last of the three expected to be completed.

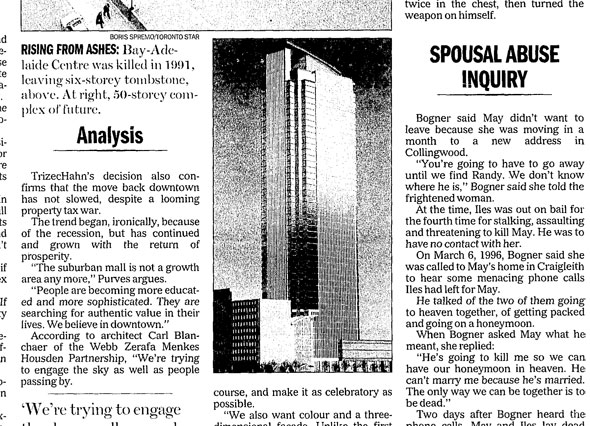

Things started to go wrong in 1991. After failing to secure an anchor tenant for the main tower, Markborough Properties (the real estate arm of HBC) and Trizec Properties decided to put the Bay-Adelaide Centre on a two-year hiatus. They called it "a sign of the times." Experts predicted vacancy rates would hit 20% in the next few years.

All that had been built above ground was the first six storeys of the central elevator core. Work was expected to resume in 1994 in a better rental market but, in 1993, the $1 billion project was axed for good, leaving the concrete block a "monument to the over-expansion of the 1980s," in the words of reporter David Crane.

"When word came ... that the Bay-Adelaide Centre had been killed, it came as a surprise to many that it had still been alive," Christopher Hume wrote in 1993.

The

city received its promised benefits despite the death of the project.

The $5 million Cloud Gardens with its thundering waterfall and enormous

textured grid, a monument to construction workers by artist Margaret

Priest, was built where there was once a severe-looking parking garage.

The

city received its promised benefits despite the death of the project.

The $5 million Cloud Gardens with its thundering waterfall and enormous

textured grid, a monument to construction workers by artist Margaret

Priest, was built where there was once a severe-looking parking garage.The space for assisted housing was also delivered in the form of the old Sears warehouse on Mutual Street (the city later sold it into private hands for $2 million, a fraction of its value, and it was converted into lofts.)

As the years passed, the bones of the ill-fated mega-project remained beautifully illuminated at night. Builders added spotlights to the structure during construction and they remained active as late as 1995, casting a brilliant light on the streaked and stained exterior. In 1996, the south side of the stump was painted to look like a cliff face, complete with ropes and a 3D climber.

The Bay-Adelaide Centre sprung to life again in March 1998 with a new design from Webb Zerafa Menkes Housden architects (the designers behind the earlier proposal) that did away with the spire and trimmed some of the height. The planned east tower was nixed, too, but the project stalled again in April 2001, still unable to attract an anchor tenant.

On the bright side, the parking lot remained a useful source of income. The revenue from its 1,100 spaces generated a 3% return for the building's owners in 2001.

It would take until 2006 for the stump to finally get the chop during construction of the west tower of the current incarnation of the Bay Adelaide Centre. Mayor David Miller and Brookfield Properties' Ric Clark swung ceremonial sledgehammers at a specially marked target on the outside of the building, signalling its imminent demolition.

The second phase of the Bay Adelaide Centre, which was announced in 2012, will - if third time really is a charm - result in a tower where concrete block once stood within the next couple of years.

Please share this

Please share this

No comments:

Post a Comment