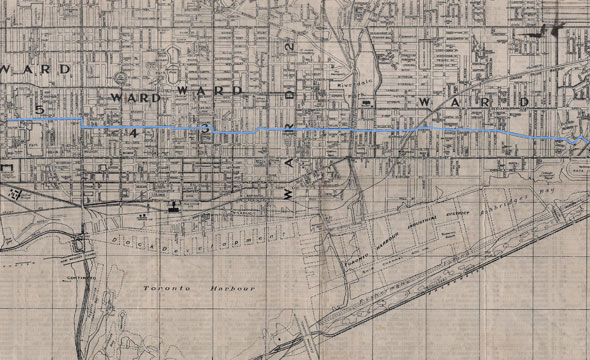

As an east-west thoroughfare, Dundas Street in Toronto is rather unusual. Even at ground level, numerous jogs, kinks and gentle curves in the road give the street a crooked, doglegged feel not found in the ruler-straight Bloor or Queen streets. The main reason for Dundas' odd route is its origin as several unconnected streets through the centre of the city. For many years, there was no major east-west street between College and Queen.

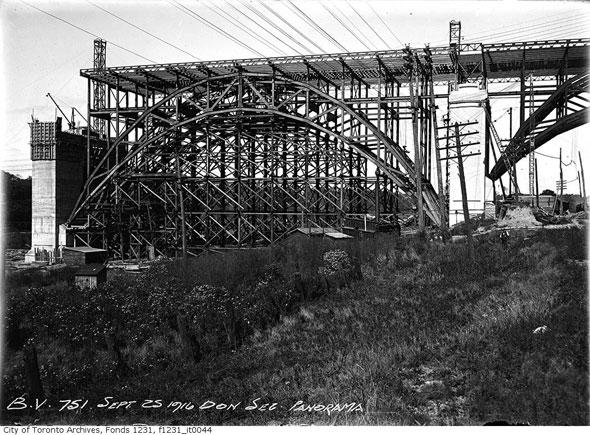

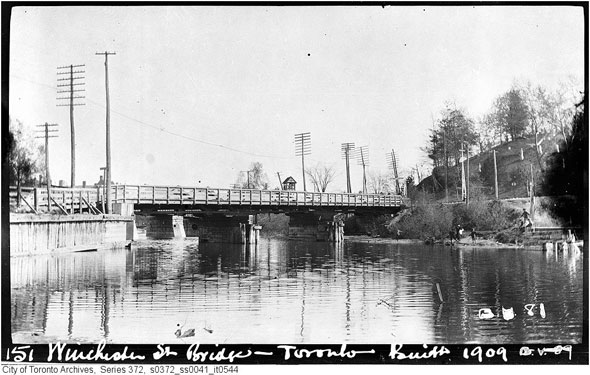

The street we know today was gradually stitched together from west to east starting around the time of the first World War. When Dundas arrived, numerous smaller streets and intersections - including a now-impossible Queen and Dundas junction - were eliminated or renamed. Without the arrival of the new street, the Dundas bridge over the Don would still be Wilton Square and Wilton Street Bridge. Yonge-Dundas Square might be something else altogether.

According to Sean Marshall at Spacing magazine,

it's a common misconception that Dundas is named for the town of Dundas

in western Ontario--its ultimate destination. In fact, Marshall writes,

the town is named for the road, which was named for Henry Dundas, a British Secretary of State.

According to Sean Marshall at Spacing magazine,

it's a common misconception that Dundas is named for the town of Dundas

in western Ontario--its ultimate destination. In fact, Marshall writes,

the town is named for the road, which was named for Henry Dundas, a British Secretary of State.Arriving from the west, Dundas used to angle south at its intersection with Ossington Avenue to intersect with Queen Street (shown above.) The section of Ossington south of Dundas today was renamed when Dundas diverted east.

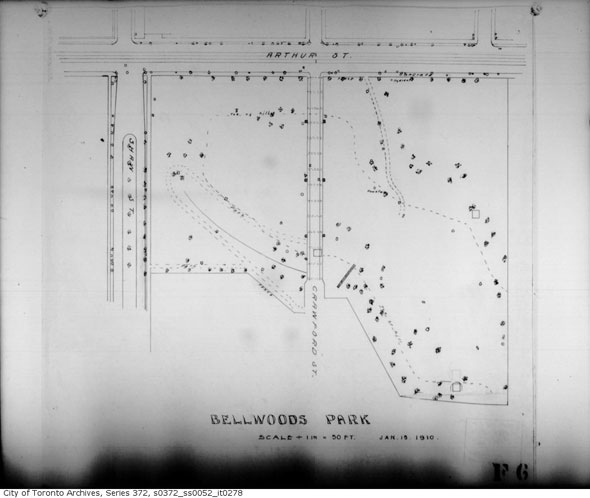

Between Ossington and Bathurst, Dundas took over a stretch known as Arthur Street that passed north of Trinity Bellwoods Park. Arthur itself had been extended west from Manning (formerly Hope Street) at a cost of $2,350 in 1883 through the property of Edward Oscar Bickford - whose daughters gave their names to Beatrice and Grace streets - and over the grounds of Trinity College.

Arthur Street terminated at Bathurst opposite a large property known simply as The Hall. Once owned by Sir Casimir Gzowski, the sprawling, well-manicured plot with its large home was once the nexus of social life in Toronto, thanks to its famous lawn parties. After Gzowski's death in 1904, the property was sold and carved up to create Alexandra Park and the site of the Toronto Western Hospital. A new road, St. Patrick Street, was created between Bathurst and McCaul through the property.

When Dundas Street arrived, a slight jog between Arthur and St. Patrick streets had to be removed, resulting in the significant kink near Denison Avenue. At the Grange, when it was still St. Patrick Street, the road sliced off roughly a third of the old property when it cut through to reach McCaul, formerly Renfrew Street. The severed slice of the Grange became housing.

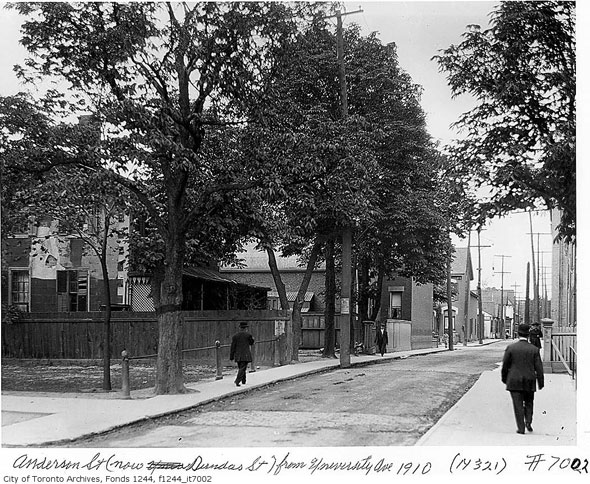

At McCaul, Dundas had to make another slight southward deviation to connect with and absorb Anderson Street, a little road to University Avenue (below). The route correction is visible today at St. Patrick Street - a road formerly known as Dummer - which received its name presumably as compensation for the loss of the old St. Patrick. Adding a chicane to Dundas better aligned it with Agnes Street, a road running east from University Avenue, though another slightly staggered intersection was still necessary.

Like old St. Patrick Street at Bathurst, Agnes Street terminated in a T-junction at Yonge Street. To continue east, drivers had to turn south on Yonge then immediately left onto Wilton. Between Yonge and Victoria, Wilton Street was dubbed Wilton Square. The name would later be changed to Dundas Square to reflect the street's new name - this portion of the street lives on in the southern edge of today's Yonge Dundas Square.

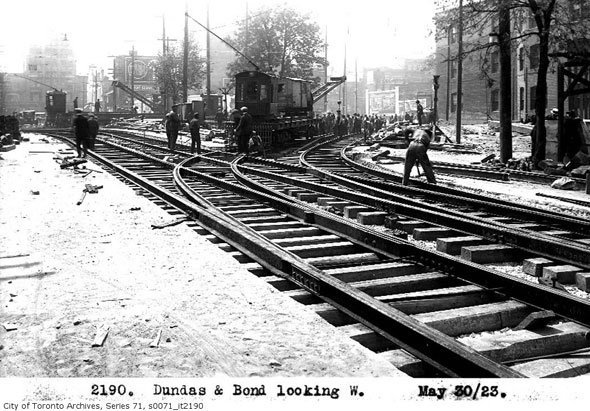

To ease passage for cars and streetcars over Yonge, the city created another significant deviation west of Bond (above). In 1998, the north side of Dundas Square would be opened up to create Yonge-Dundas Square as we now know it.

Continuing east, the defining characteristic of Wilton Avenue was Wilton Crescent, a gentle curve in the road that once formed the northern boundary of Moss Park. The curve is still there, exactly as it was, between Filmore's Hotel and Sherbourne. Moss Park is now considerably smaller and tucked well to the south and the surrounding neighbourhood, once affluent, has fallen on hard times.

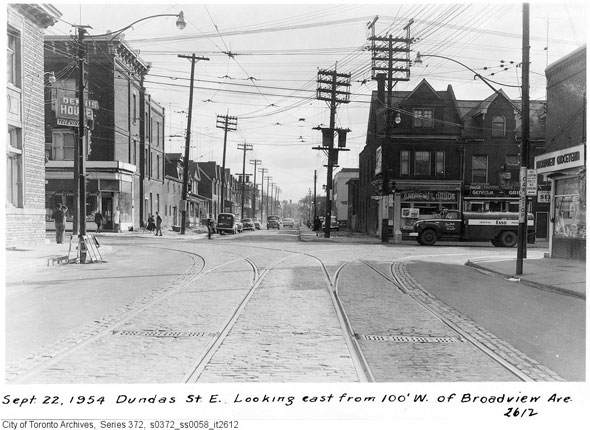

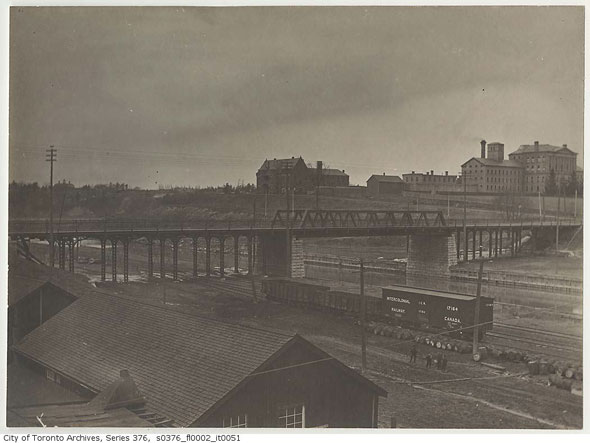

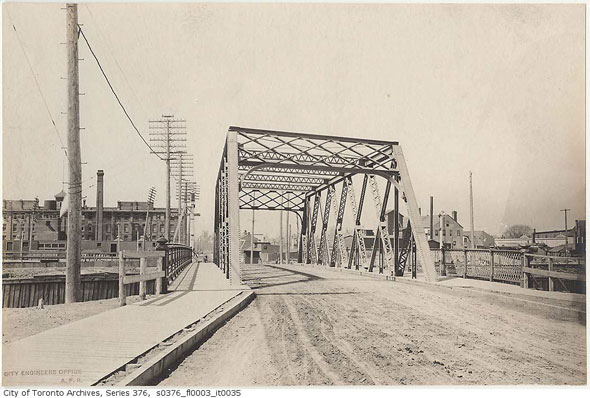

Dundas claimed the remainder of Wilton Avenue - east of Wilton Crescent, over the Don to Boulton Avenue, just past Broadview. As I wrote last week, the bridge over the river was originally named for Wilton Avenue before Dundas arrived. It was here, at Riverside, that the new street terminated until after the second World War.

When Dundas was extended further east to its present terminus at Kingston Road, the city decided to incorporate several minor roads and even some laneways. As Sean Marshall says in his Spacing piece, many houses still have garages on Dundas near Jones as a result of that plan.

Moving east between Boulton and Jones, Whitby and parts of Dagmar were strung together to allow Dundas to reach Doel Avenue. Interestingly, the diagonal part of Dundas below Greenwood isn't one of the many deviations that line the street - it was present in 1916 too.

In its final stretch past Greenwood, Dundas was built out of Applegrove Avenue, Ashbridge Avenue, Maughan Crescent, and Hemlock Avenue, which were built around Small's Pond, a long-lost body of water just north of Queen and Kingston.

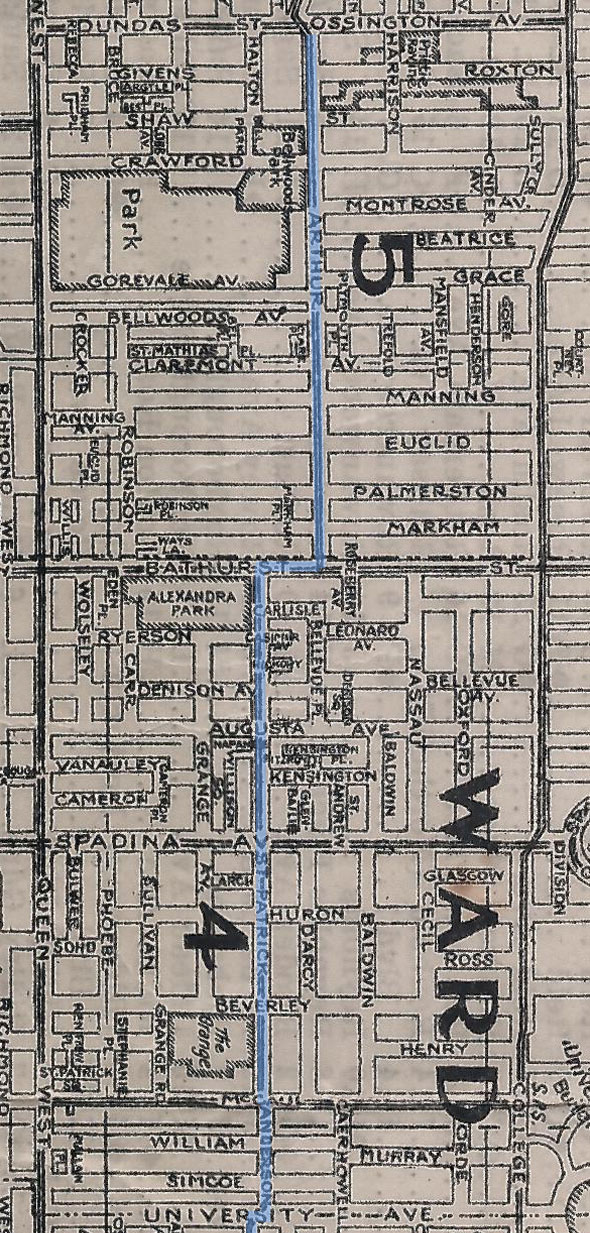

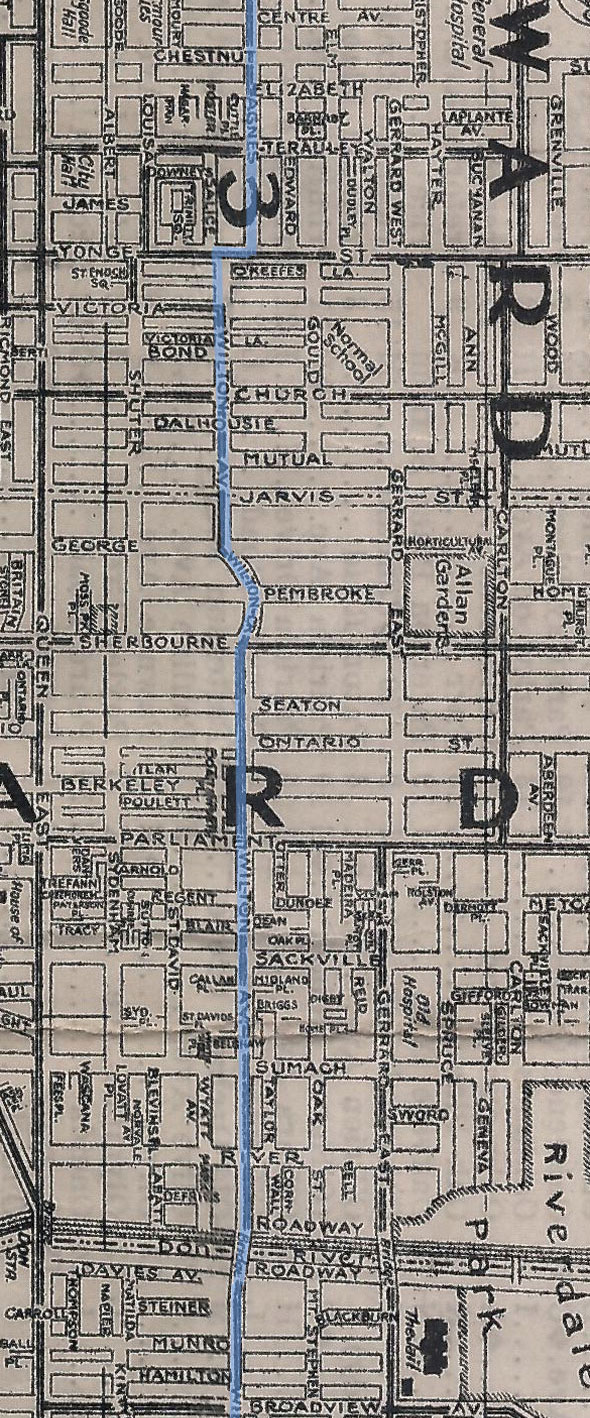

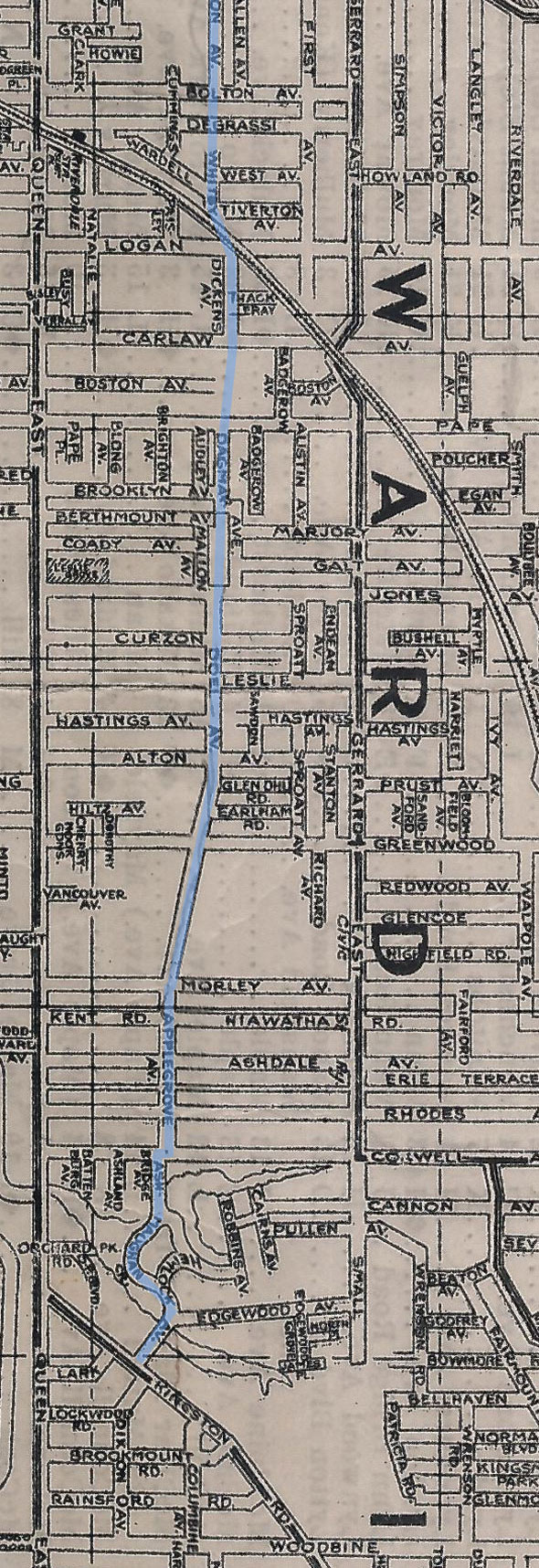

In all, Dundas Street links 15 former streets in its kinked route across the city. If you're having visualizing all of this, click here for a map of the route (rotated ninety degrees) between Ossington and Kingston Road.

MAP

Ossington to University

University to Broadview

Broadview to Woodbine

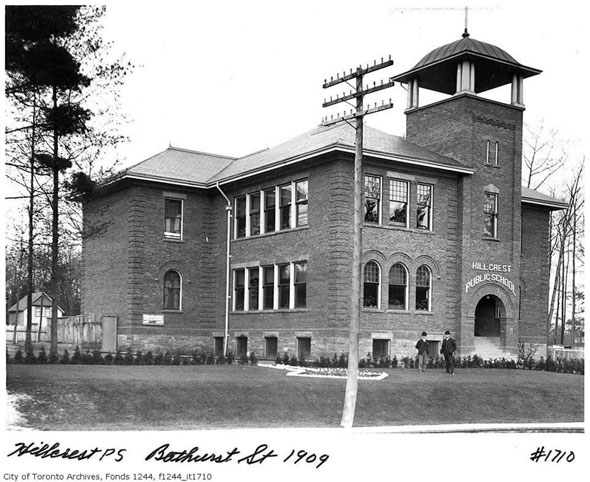

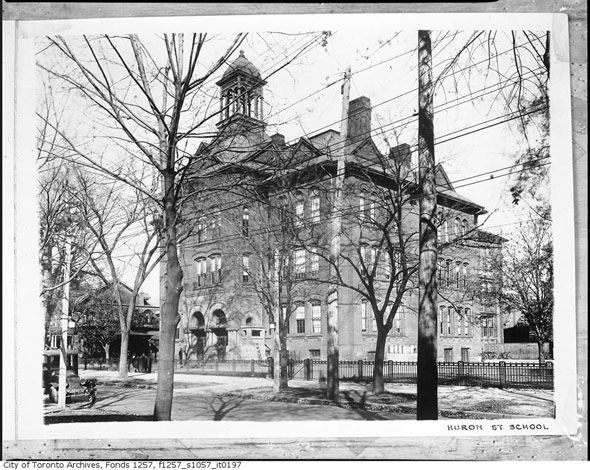

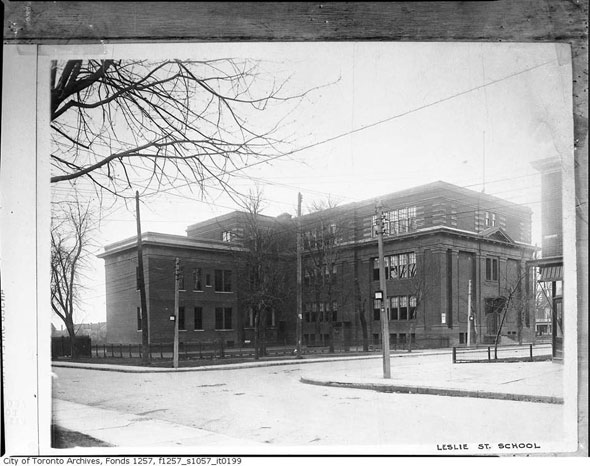

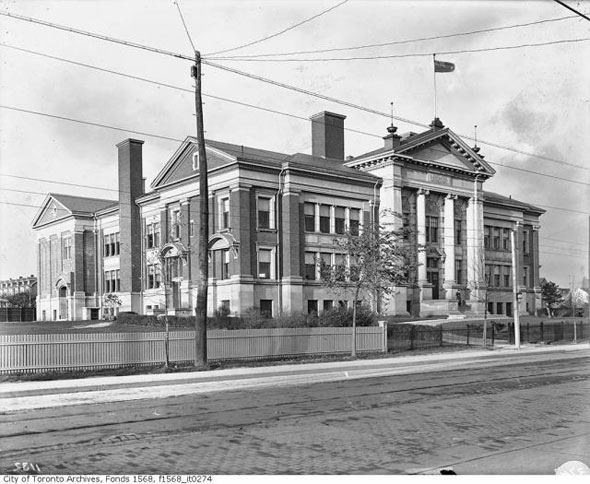

Photos: City of Toronto Archives and University of Toronto

Thundering

over the Don Valley on a westbound subway train it's easy to

underestimate the shining river below. In numerous locations - Bloor,

Gerrard, Dundas, Queen, Eastern, and the Gardiner - it's possible to

entirely skip over the lower Don without so much as a bump in the road.

Man one, nature nothing.

Thundering

over the Don Valley on a westbound subway train it's easy to

underestimate the shining river below. In numerous locations - Bloor,

Gerrard, Dundas, Queen, Eastern, and the Gardiner - it's possible to

entirely skip over the lower Don without so much as a bump in the road.

Man one, nature nothing.

Continuing south, the next major crossing point is

Continuing south, the next major crossing point is

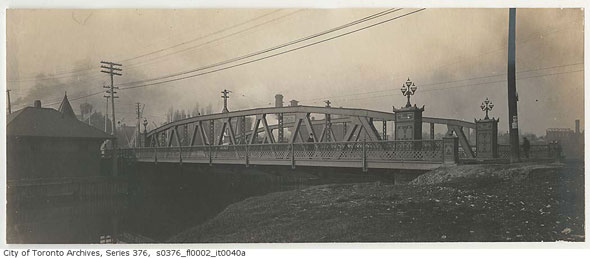

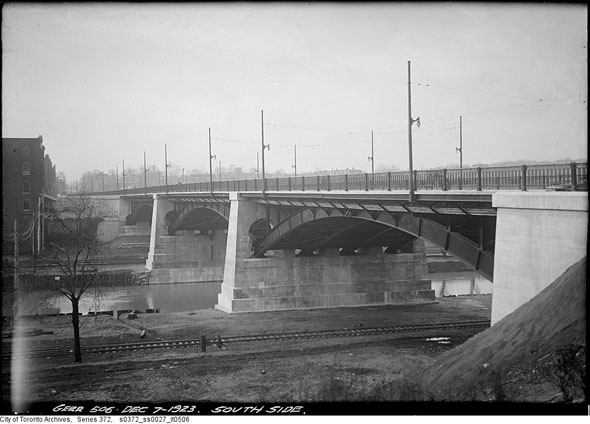

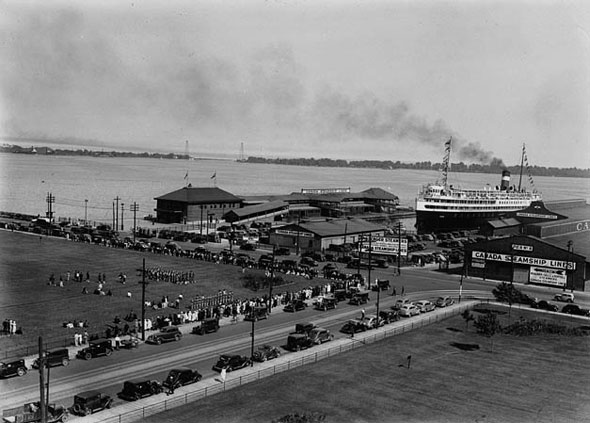

The newly completed Gerrard Street bridge.

The newly completed Gerrard Street bridge.

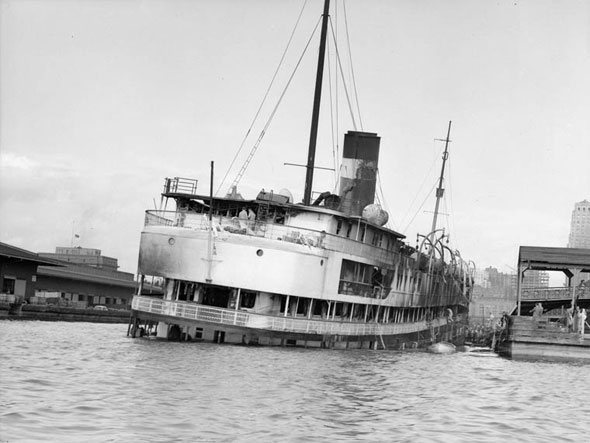

Unfortunately, as you might suspect, things didn't entirely go to plan.

Unfortunately, as you might suspect, things didn't entirely go to plan.

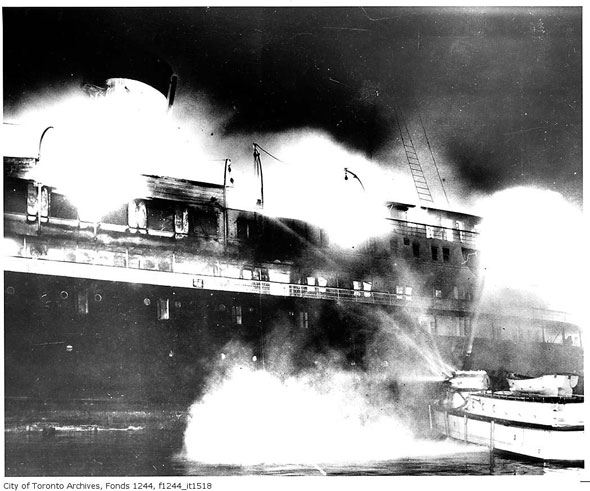

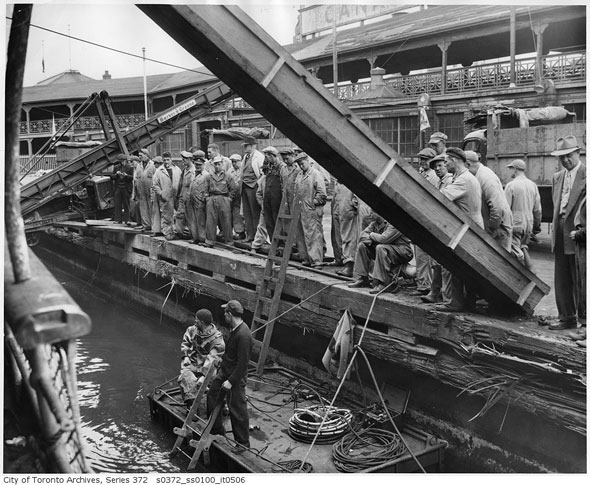

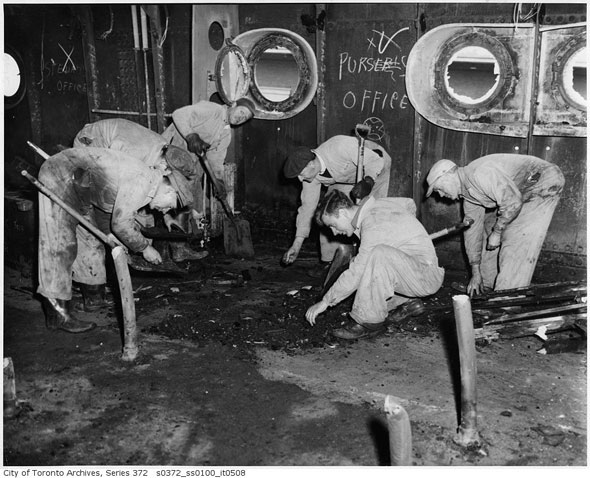

Investigators line the dock before entering the hull of the Noronic

Investigators line the dock before entering the hull of the Noronic

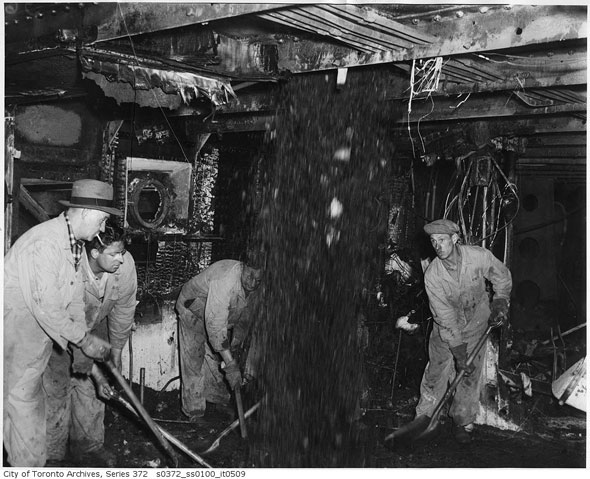

Investigating an area of interest in what was the purser's office

Investigating an area of interest in what was the purser's office

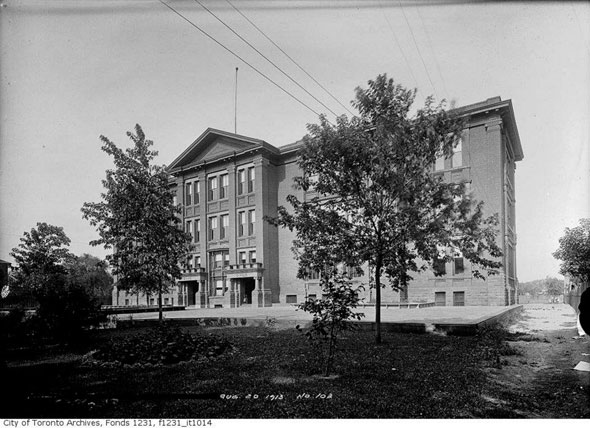

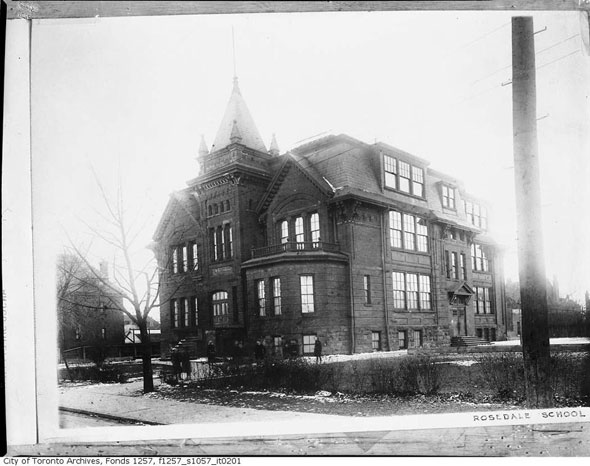

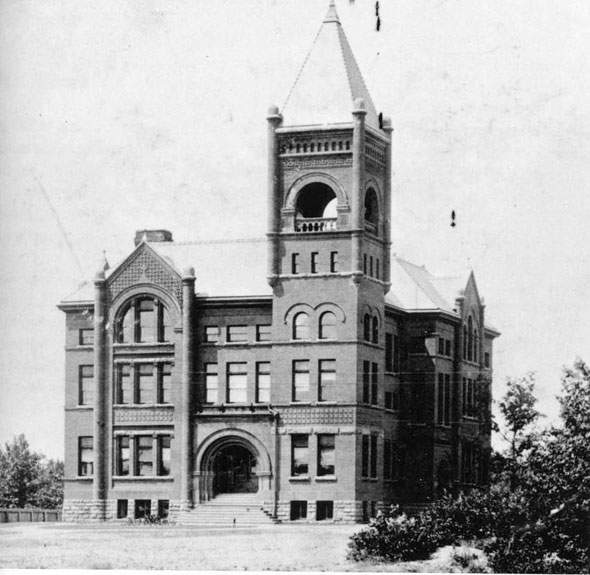

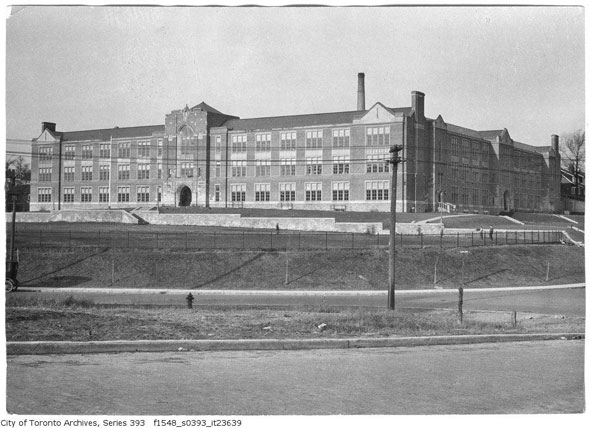

Agincourt CI

Agincourt CI

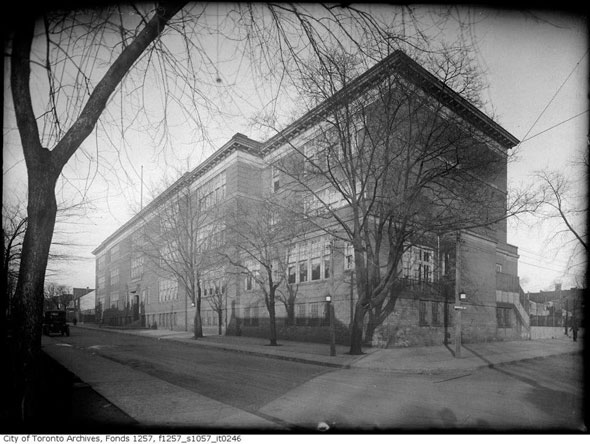

Broadview Avenue School

Broadview Avenue School

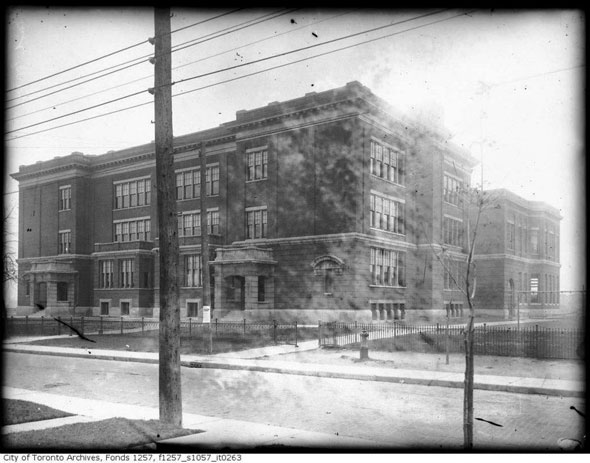

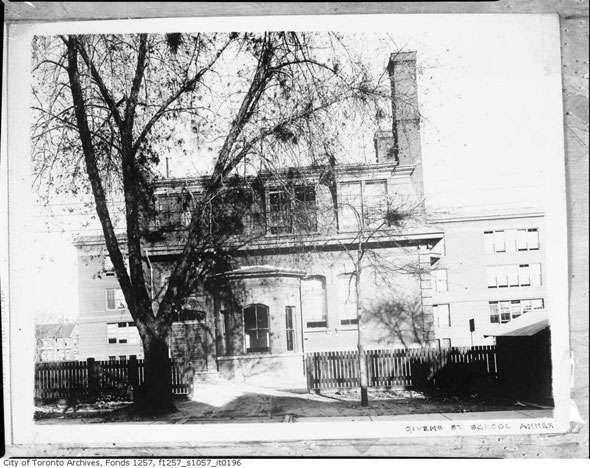

Wilkinson Public School

Wilkinson Public School