When

Dr. Charles Hastings became Toronto's medical officer of health in

1910, the city was rife with disease. Hundreds needlessly died each year

of typhoid fever, scarlet fever, and diphtheria, and the infant

mortality rate was alarmingly high - Hastings' own daughter died as

infant after drinking milk from a typhoid-infected farm.

When

Dr. Charles Hastings became Toronto's medical officer of health in

1910, the city was rife with disease. Hundreds needlessly died each year

of typhoid fever, scarlet fever, and diphtheria, and the infant

mortality rate was alarmingly high - Hastings' own daughter died as

infant after drinking milk from a typhoid-infected farm.In the wake of his personal tragedy, the white-haired, moustachioed physician turned his attention to improving Toronto's public health at 52 when others in his situation would be preparing for retirement. Focusing on food safety standards, nutrition, and public housing, Hastings fought hard and won a 1,000% increase in the city's health budget, swelling the team from 70 to around 500 workers during his tenure.

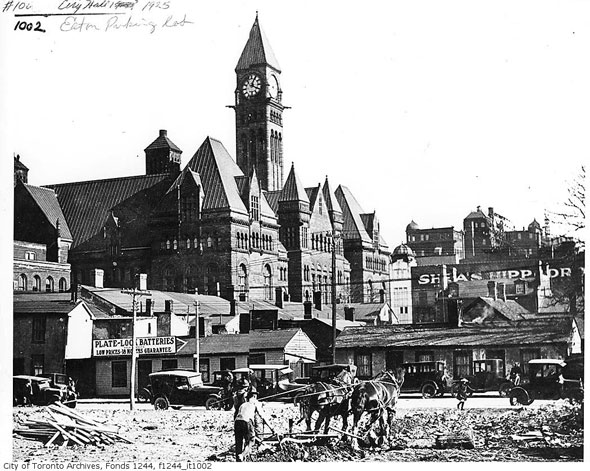

A

year after Hastings took office, Toronto's poorest neighbourhood was

The Ward, a dense cluster of timber-framed homes on the land now

occupied by City Hall, the Superior Court of Justice, and The Hospital

for Sick Children.

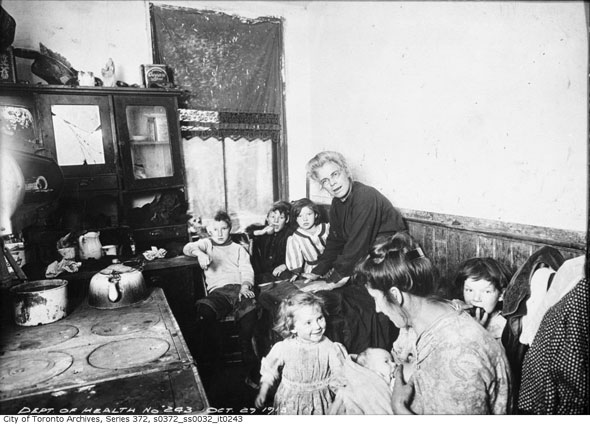

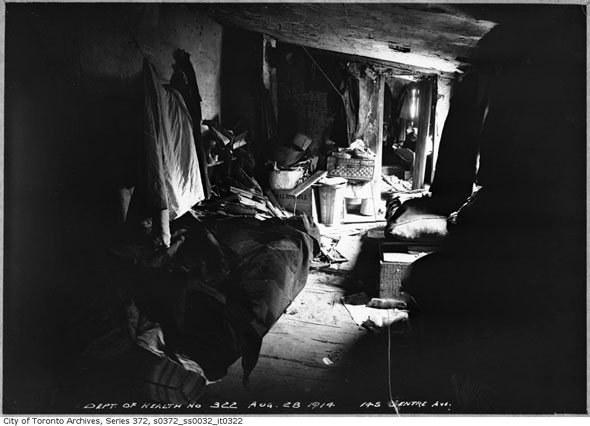

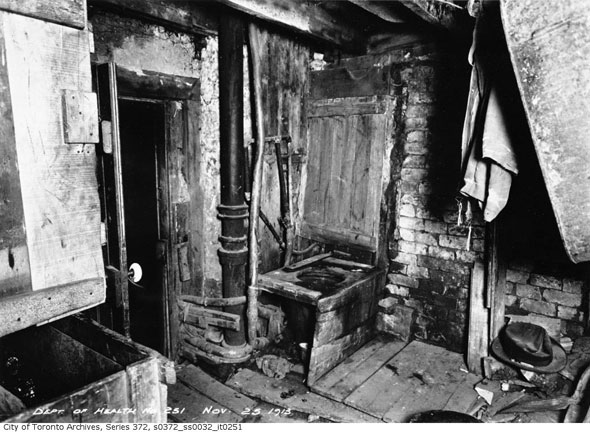

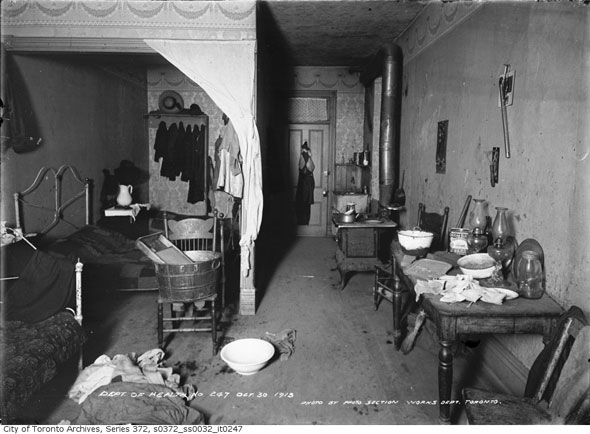

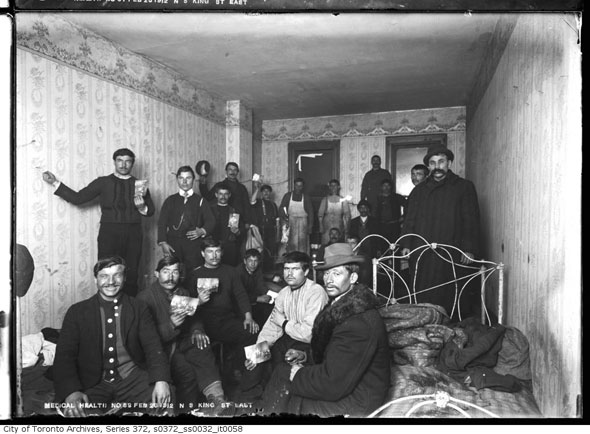

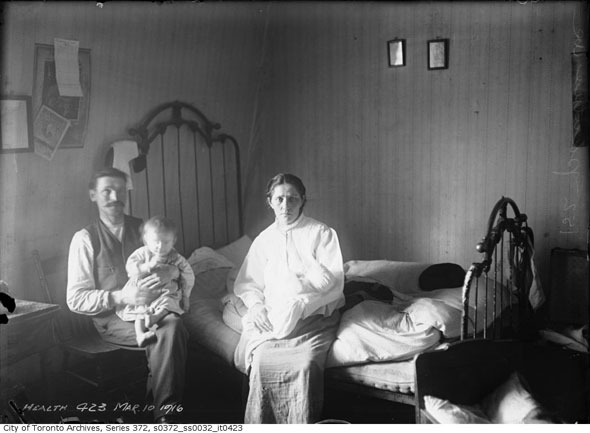

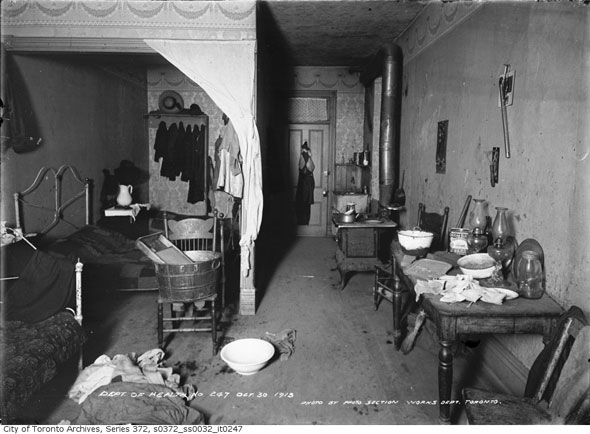

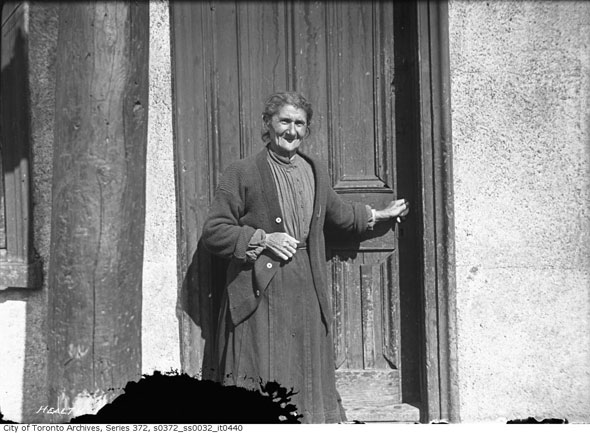

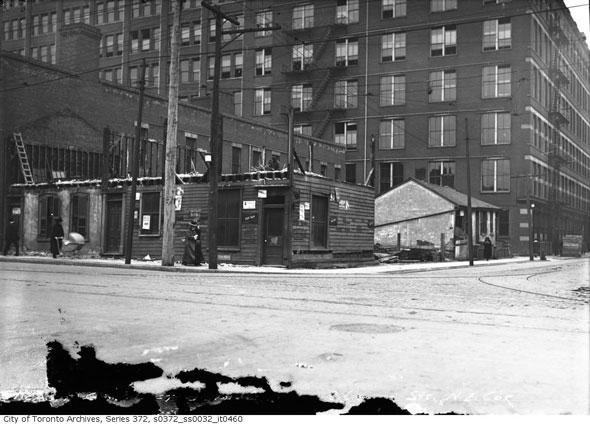

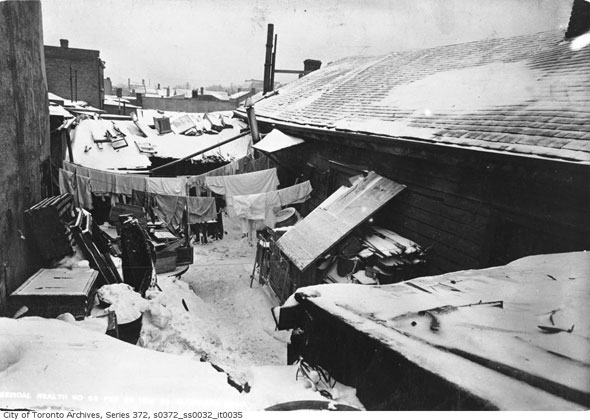

A

year after Hastings took office, Toronto's poorest neighbourhood was

The Ward, a dense cluster of timber-framed homes on the land now

occupied by City Hall, the Superior Court of Justice, and The Hospital

for Sick Children.It was here poor new immigrants from Europe, particularly Austrian, Polish and Russian Jews, sought shelter in overcrowded, ramshackle rooms. Almost a quarter of the inhabitable buildings housed 10 or more people, often in unimaginable squalor: outdoor toilets overflowed with excrement, animals and humans slept side-by-side in damp, windowless basements, and families huddled in filthy backyard shanties.

Just

30 years earlier, St. John's Ward was like much of Toronto: populated

by working class Protestants from England, Ireland, or Scotland. Many

worked in skilled professions, like shoemaking or tailoring at the

neighbouring T. Eaton Co. factory, or owned businesses.

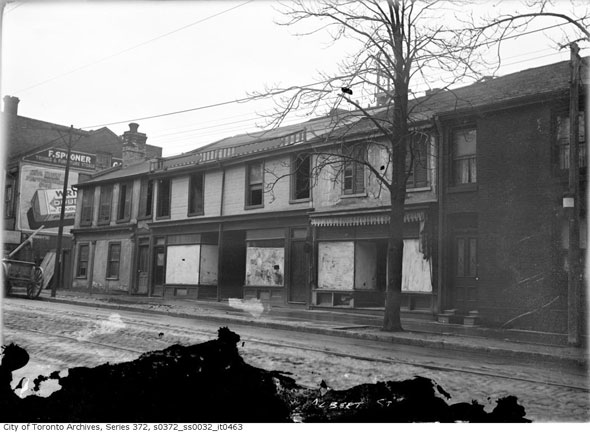

Just

30 years earlier, St. John's Ward was like much of Toronto: populated

by working class Protestants from England, Ireland, or Scotland. Many

worked in skilled professions, like shoemaking or tailoring at the

neighbouring T. Eaton Co. factory, or owned businesses.Around the turn of the century the character of The Ward changed significantly. Overcrowding increased as homes were knocked down for civic buildings like Old City Hall and new arrivals were forced in to ever shrinking spaces by discrimination and xenophobia. Hastings studied the area and poor housing conditions in other parts of the city, producing a seminal report on slum conditions.

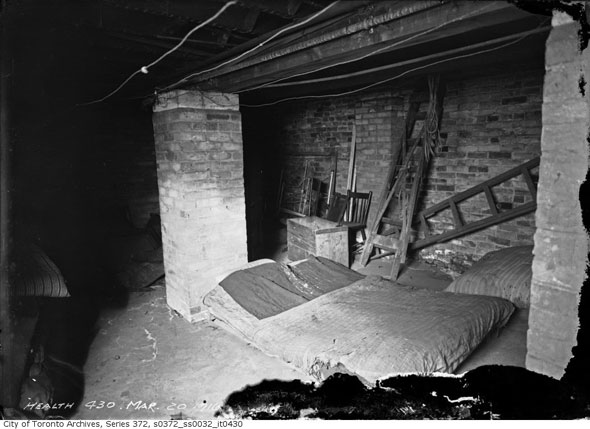

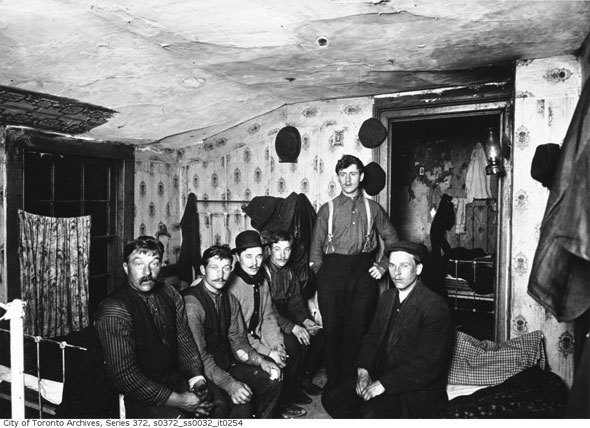

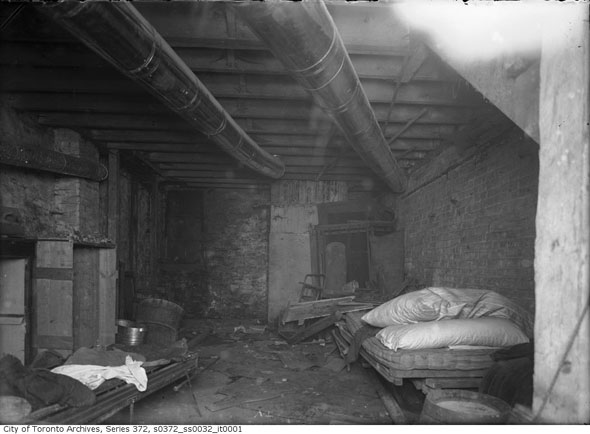

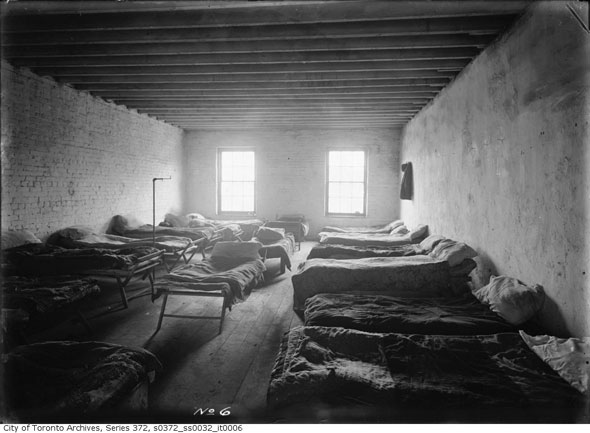

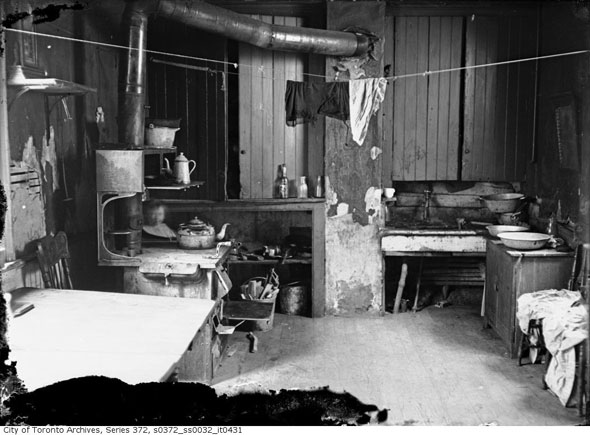

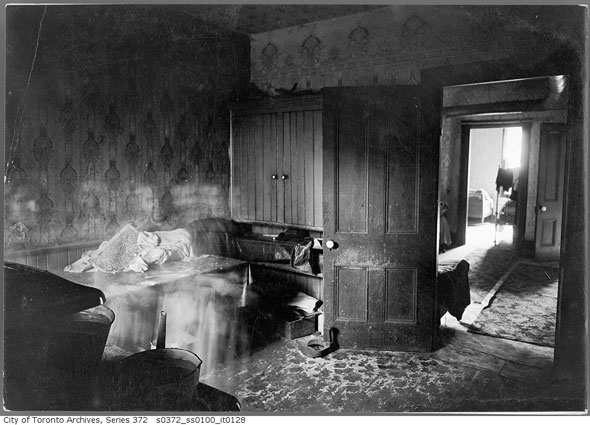

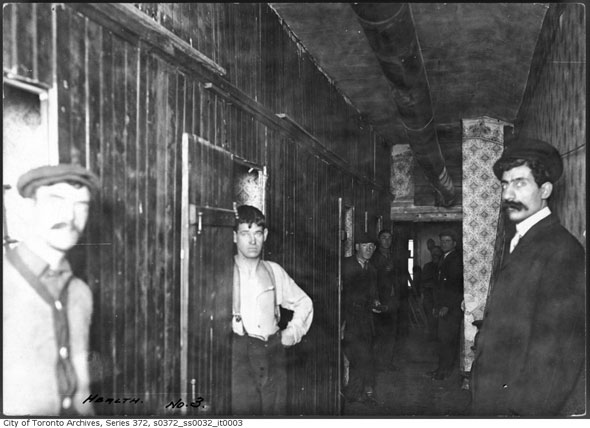

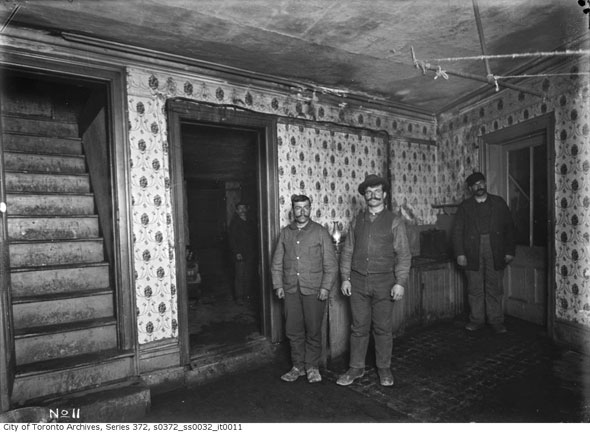

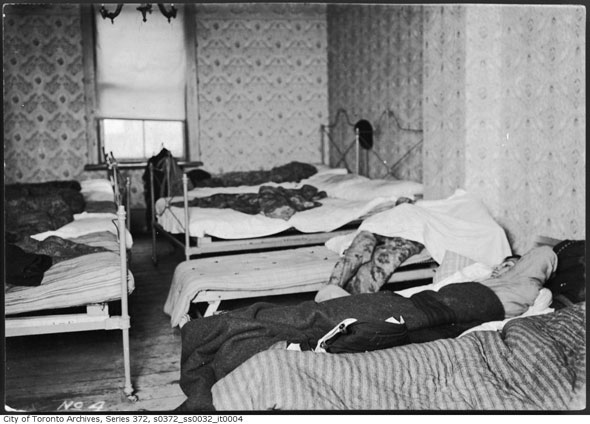

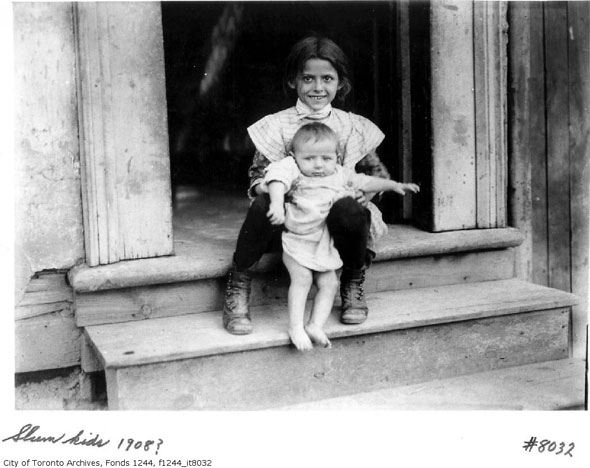

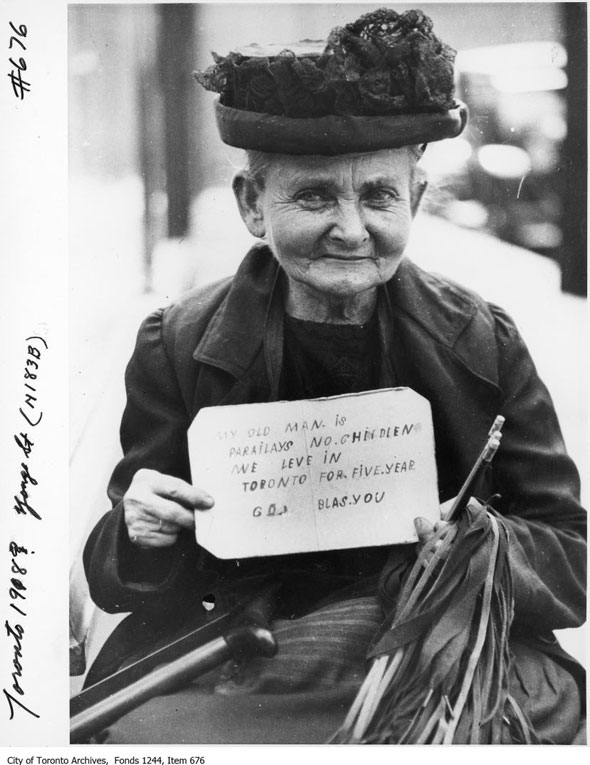

The

photographs that accompanied his inspection of more than 5,000

dwellings shine a powerful light on poverty in Toronto in the early part

of last century. The six men in the picture above, recent Polish

immigrants, shared two tiny connected upstairs rooms at 50 Terauley

Street, now Bay Street. Hastings' staff estimated the room was suitable

for three at most.

The

photographs that accompanied his inspection of more than 5,000

dwellings shine a powerful light on poverty in Toronto in the early part

of last century. The six men in the picture above, recent Polish

immigrants, shared two tiny connected upstairs rooms at 50 Terauley

Street, now Bay Street. Hastings' staff estimated the room was suitable

for three at most.A bed typically cost 75 cents to $1.25 per week out of a salary of around $1.75 to $3.50 per day.

In

his report, Hastings called the slums "a menace to public health" and

"an offence against public decency." He railed against unscrupulous

landlords who refused to make sanitary improvements and preyed on

vulnerable new immigrants but didn't pull punches when it came to the

behaviour of nuisance tenants.

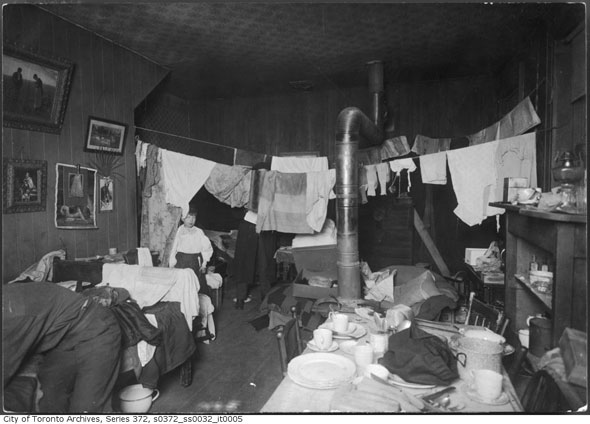

In

his report, Hastings called the slums "a menace to public health" and

"an offence against public decency." He railed against unscrupulous

landlords who refused to make sanitary improvements and preyed on

vulnerable new immigrants but didn't pull punches when it came to the

behaviour of nuisance tenants."They live cheap, work out all day, crowd into the houses at night, bring the mud of the streets into their homes, drink beer, play cards, and sleep, in the clothing worn during the day, in closed rooms," he wrote of a house of European immigrants. "No cleaning ever attempted until brought to court."

In the years that followed more than 1,600 of the worst homes were razed by the city and public health programs were introduced piecemeal until 1929, when Hastings retired aged 70.

MORE IMAGES:

Please share this

Please share this

No comments:

Post a Comment