The

2014 men's Olympic hockey squad is a super team of NHL stars from

across the country. As the most talented and highly paid individuals in

their field, they are the Traveling Wilburys of hockey, if you will -

the team could never exist if it hadn't been created.

The

2014 men's Olympic hockey squad is a super team of NHL stars from

across the country. As the most talented and highly paid individuals in

their field, they are the Traveling Wilburys of hockey, if you will -

the team could never exist if it hadn't been created.90 years ago, it was a group of talented amateurs from Toronto who fought for, and eventually took home, Canada's first (and the world's first) winter Olympic gold in hockey at the 1924 Chamonix Olympics. With devastating efficiency they tore through the competition, scoring in bunches. The opposition didn't stand a chance.

The

Toronto Granite Curling Club was founded by an act of rebellion. Five

of prominent members of the Toronto Curling Club - two bankers, a

politician, a lawyer, and a businessman - decided in 1875 that they were

fed up with the sports society's plan to build a new enclosed rink on

Adelaide Street.

The

Toronto Granite Curling Club was founded by an act of rebellion. Five

of prominent members of the Toronto Curling Club - two bankers, a

politician, a lawyer, and a businessman - decided in 1875 that they were

fed up with the sports society's plan to build a new enclosed rink on

Adelaide Street. The economy was struggling and many of its members viewed the arena as an unnecessary extravagance, record authors Rod Austin and Ted Barris in Carved in Granite: 125 Years of Granite Club History.

With the help of some 30 prominent members, a splinter group was formed. There was William Mellis "Mr." Christie, the namesake of Christie St., Robert Henry Bethune the first general manager of the Dominion Bank, and Robert Jaffray the director of The Globe newspaper, among others.

The first members would soon be joined by Toronto mayor W.B. McMurrich and J.D. Edgar, the speaker of the House of Commons. Sir John A. Macdonald was an honorary patron.

The founders named their new club after the dark grey rock of the Canadian Shield used in their curling stones.

The Granite Club's "uptown" clubhouse, a single-story wood hut surround by an ice sheet, was one of just three curling rinks in the city, and it quickly became a magnet for anyone of a sporting bent. It was also the only club located away from the waterfront, the frozen surface of which became a perfect natural ice sheet in winter.

The Granite Club expanded to a new two-storey red brick premises on Church Street in 1880. At the building's rear sat a massive enclosed rink with enough room for four curling sheets. Before the arrival of artificial ice and Zambonis, simply creating a rink big enough for the club members' needs was a serious undertaking.

"The poor, long-suffering ice man would sit up night after night, waiting for the temperature to drop. When it did, he would throw open the large doors of the rink, don his leather gloves and high rubber boots, and begin sprinkling the floor of the rink with water, adding a little more each time as it froze," Rod Austin and and Ted Barris write.

"Then, using hot water from a watering can, he would 'pebble' the surface to produce a beautiful checkerboard appearance. Ice making in the 19th century was not only hard work, it was also an art."

The

Granite Club's various curling teams had plenty of success but it was

its men's hockey team that would make the biggest sporting impact.

The

Granite Club's various curling teams had plenty of success but it was

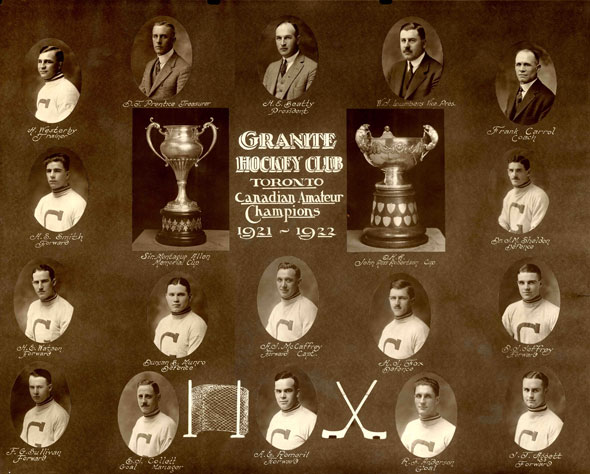

its men's hockey team that would make the biggest sporting impact.In the early 1920s, the Toronto Granites were an emerging force in the Ontario Hockey Association. Under the guidance of Toronto Star sports editor William A. Hewitt, father of broadcaster Foster Hewitt, the team won the 1920 John Ross Robertson Cup, beating the Hamilton Tigers on aggregate over two games.

The team switched to the Allen Cup, the trophy awarded to the national amateur champions, in 1922, taking back-to-back wins against the Regina Victorias and University of Saskatchewan respectively.

The win against the University of Saskatchewan was particularly hard fought. The collegiate side repeatedly breached the Granites' defence only to be denied by the calm heroics of goalie Jack Cameron.

Forward Harry Watson - dubbed the "bad man" in the "Ambitious City" - scored the first goal for the Granites in front of some 6,000 rabid Winnipeg fans, many of whom had been in line for tickets since before dawn. Hard work over two games by captain Dunc Munro and forward "Hooley" Smith proved pivotal, leading to a 11-2 final score after two games.

As was customary until 1960, the Allen Cup champions in an Olympic year were automatically selected to represent Canada against the world.

1924

was a special year for the Olympics as it was. For the first time in

the modern era, the event would be divided in two: one event for summer

sports, another for winter, both played in the same country a few months

apart.

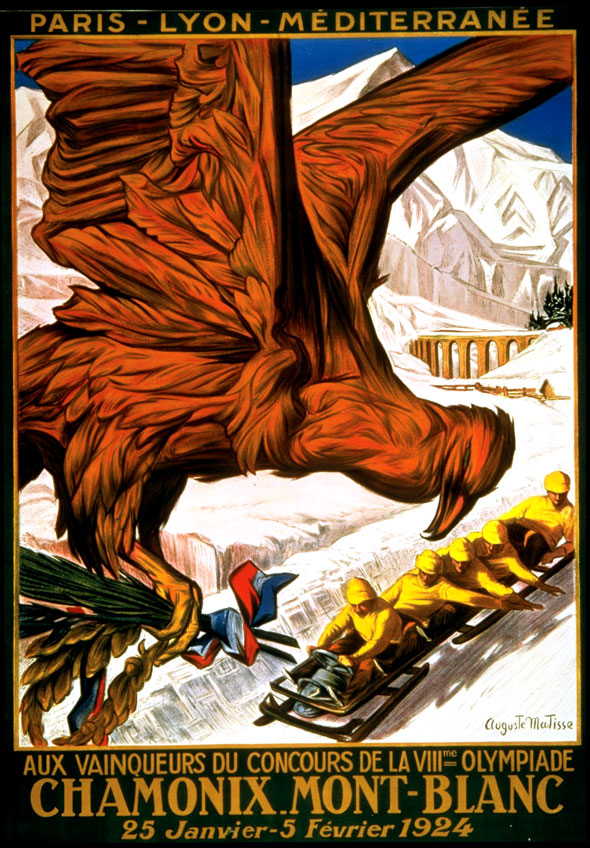

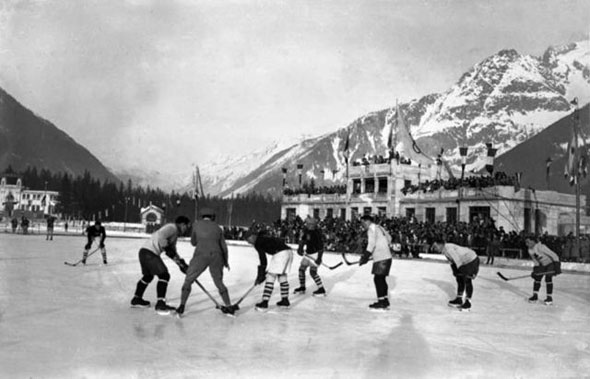

1924

was a special year for the Olympics as it was. For the first time in

the modern era, the event would be divided in two: one event for summer

sports, another for winter, both played in the same country a few months

apart.The little alpine village of Chamonix, tucked in the imposing shadow of Mount Blanc, would host hockey, bobsleigh, figure skating, and winter patrol - a cross-country combination of skiing, rifle shooting, and mountaineering that would eventually morph into the biathlon - while Paris would be the site of the summer games a few months later.

The

Toronto Granites left for Europe with several new players aboard the

RMS Montcalm on Jan. 11, 1924. A vicious winter storm had whipped the

Bay of Fundy into a nauseating froth. Forward "Hooley" Smith bet Toronto Evening Telegram

writer Harry Watson that he wouldn't be seasick, and lost. The next

morning only three of the nine-man squad made it to breakfast.

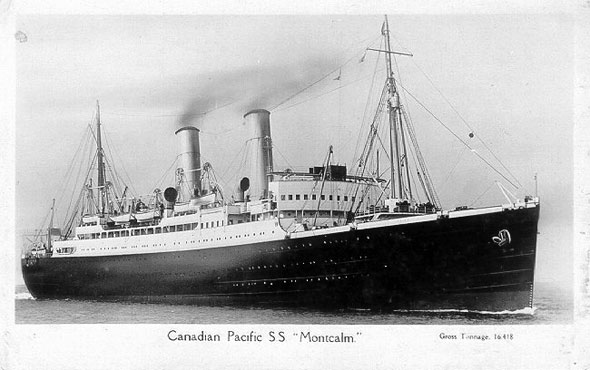

The

Toronto Granites left for Europe with several new players aboard the

RMS Montcalm on Jan. 11, 1924. A vicious winter storm had whipped the

Bay of Fundy into a nauseating froth. Forward "Hooley" Smith bet Toronto Evening Telegram

writer Harry Watson that he wouldn't be seasick, and lost. The next

morning only three of the nine-man squad made it to breakfast. "[Dunc Munro] was afraid he was going to die; the next day he was afraid he was not going to die," Watson wrote.

The team arrived in Chamonix via London and Paris and were clearly impressed by what they found. William A. Hewitt cabled his bosses at the Toronto Star gushing over the "towering mountains," the glaciers, and the mountain stream that bisected the village.

Also writing for the Star and quoted in Carved in Granite: 125 Years of Granite Club History, captain Dunc Munro sketched out the team's day-to-day activities:

"Mr. Hewitt has the boys under strict discipline. They are to retire at ten o'clock and rise for an eight o'clock breakfast. I may say that by ten o'clock they are all glad to go to bed, as the wonderful air here makes you very tired ... Chamonix is the St. Moritz of France. There are many things to do here, but most of them are out of bounds until after we win the world's championship."

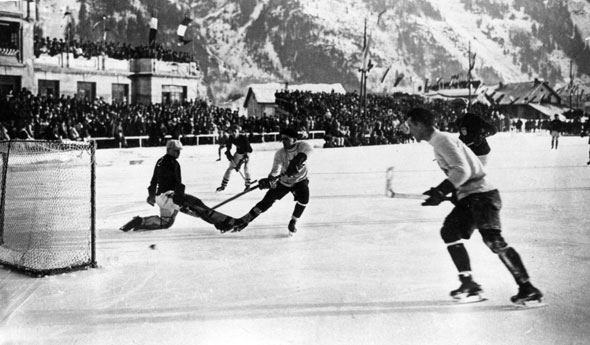

The Olympic hockey games were played outdoors on a natural European-size ice rink, which was considerably bigger than what they were used to in Canada. The Granites were also forced to adapt to tiny 1-foot boards that eliminated heavy body checks and practically all dump-ins. The main hockey stadium was "twice as large at the University of Toronto stadium" and could hold about 5,000 people.

They needn't have been worried by the unfamiliar playing surface because few countries managed to mount a defence against the all-powerful OHA champs. The Granites crushed Sweden, Czechoslovakia and Switzerland without conceding a single goal. Great Britain capitulated 19-2, leaving only the United States between the Canadians and a first Winter Olympic gold.

Though

it would have made for a great story - victory in the face of defeat,

an unlikely come from behind win, etc.. - the Americans also didn't

present much of a challenge either. "The Canadians won rather easily,"

wrote the Toronto Star. "Their passing back and forward was a treat. Their teamwork was the predominant feature of the victory."

Though

it would have made for a great story - victory in the face of defeat,

an unlikely come from behind win, etc.. - the Americans also didn't

present much of a challenge either. "The Canadians won rather easily,"

wrote the Toronto Star. "Their passing back and forward was a treat. Their teamwork was the predominant feature of the victory."The Granites stormed to an early two-goal lead with markers from McCaffrey and Watson in the first period. Watson, one of the most talented players on the team, faked and deked through the American defence for the second goal. Spectators called it a thing of beauty.

A deflected shot beat Canadian goalie Jack Cameron for the only American point moments later. Three goals in the second and another in the third from Munro, a stunning individual effort in the mould of Watson's goal earlier in the game, sealed the victory 6-1. It was never close.

Despite a cross-check bursting his lip in the first minute, Harry Watson was the undoubted star of the match. "After the game the Americans declared Watson the greatest hockeyist of all time," The Star wrote. "They said no other player ever took so much punishment and played such brilliant hockey."

Moments later, the band struck up "The Maple Leaf" and the Canadian ensign was raised to the top of the stadium.

Canada had its first hockey gold at the Winter Olympics.

Please share this

No comments:

Post a Comment