Road vehicles in Toronto first went under the command of traffic lights 88 years ago this week. Where as in 1925 just one intersection had an electric set of signals, now there are around 2,300 sets of red, yellow, and green lights - some on a sensor, some on a timer - regulating how cars, buses, streetcars, cyclists, and pedestrians move around the city.

In 1963, Toronto became the first municipality in the world to computerize its traffic operations. In the 1920s, however, the city was already playing catch-up with other cities in the province when it came to getting traffic cops and their signs out of the middle of the street.

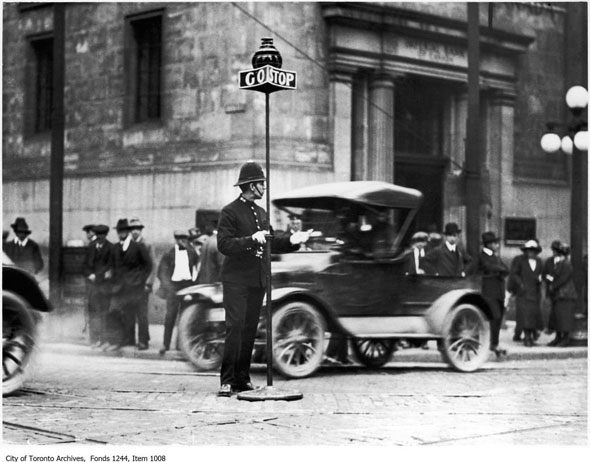

Before electric signals became commonplace, traffic at each major downtown intersection was supervised by a dedicated uniformed police equipped with a large rotating sign. Standing smack in the middle of the intersection, sometimes perilously between the streetcar tracks, the officer would spin the sign to indicate which direction should proceed.

Hundreds of American and a handful of Canadian cities - Windsor, London, Hamilton - had electric traffic signals while Toronto continued to stick with its traffic cops. It's hard now to imagine a time when regulating traffic with a set of colour-coded lights was an unusual concept in need of a detailed explanation, but it was once so in 1925.

In the mid-20s even second-hand cars still cost around $400 - $5,300 in today's money - and represented a significant investment beyond the reach of many. Despite the cost, Ford, Chevrolet, Dodge, and Jewett cars were becoming a powerful presence on Toronto's already crowded streets, and the city was keen to keep the roads organized and safe even though there were just 22 auto accidents recorded 1925.

As a result, Bloor, St. Clair, Dundas, Spadina, University and other major arterial streets were widened in the two decades following the turn of the century for additional vehicle capacity at the expense of hundreds of trees, lush grass verges, and wide sidewalks.

The Crouse-Hinds Company system chosen to conduct a test of signal technology in Toronto had been installed on the first traffic lights just over the lake in Syracuse the year before, in 1924.

In one part of the American city, Tipperary Hill, the lights were intentionally hung upside down, with the red at the bottom, in response to vandalism by Irish residents upset that the "British" colour was on top and the "Irish" on the bottom, or so the story goes. The lights there are still upside down.

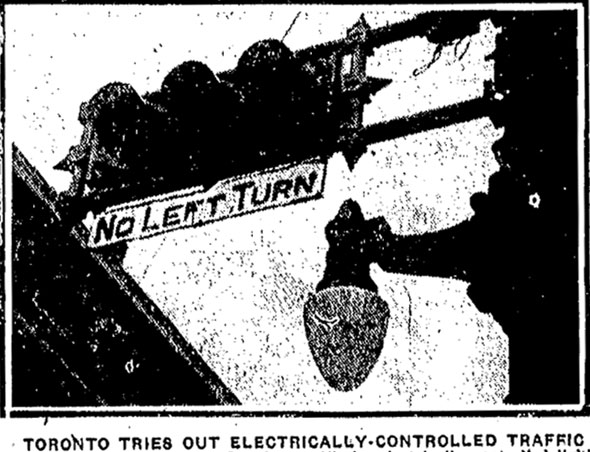

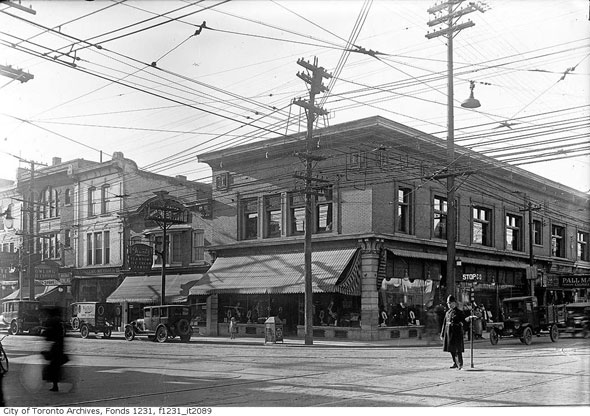

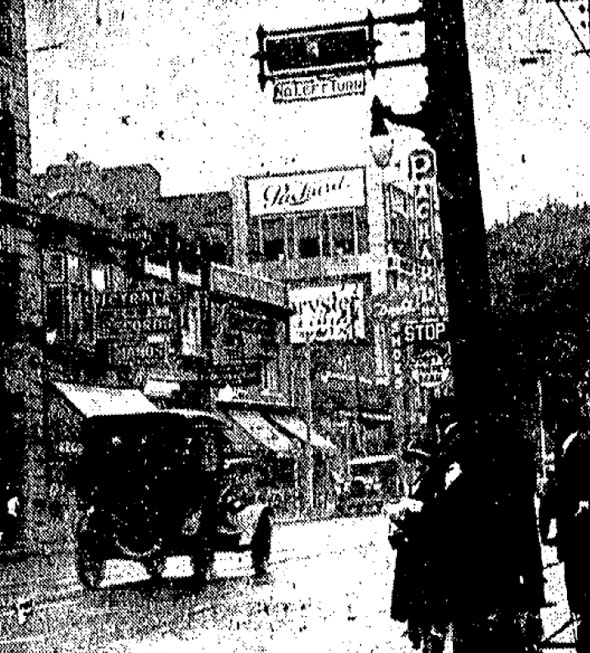

In Toronto, the lights were first arranged in a horizontal row so that red, yellow, and green were all at the same level. At Yonge and Bloor, the intersection chosen as a testing ground for the experiment (the city wasn't sure it would actually stick with the idea,) streetcars in both directions and pedestrians were required to abide by the new rules as well.

Here's how the Toronto Star explained, a little verbosely, the system of colours to wide-eyed drivers:

"... when the red light is showing on the north and south poles all north and southbound traffic ceases, when the yellow appears a warning is given to all who are approaching the intersection that the signal is about to change from "Stop" to "Go" and this interval gives a chance to those who are on the intersection to get across the street before the other traffic begins. Four lights are burning all the time, two reds and two greens or four yellow."

The first test turned out to be something of a spectacle. "A large crowd was gathered at the corner expectantly waiting for something to happen but apart from the excitement of watching the lights change in colour and laugh at the expense of some luckless motorist who was made to back across the street because he had failed to obey the signal, the watchers were disappointed," the paper noted.

In general, drivers found the concept easy to grasp despite the sudden and confusing introduction. That said, a team of four cops granted quite a few mulligans on the first day, politely explaining the rules to anyone bewildered enough to cause a blockage.

"The public took to the signals with very little trouble," Deputy Chief Constable Robert Beatty reported later in August 1925. "For the first few days it was necessary to have two men there, but now there is only one now." Parkdale residents near the intersections of Lake Shore and Jameson and Lake Shore and Dunn would be next to get automatic lights, he said.

The new technology, quaintly known as "semaphores" at first, didn't mean the city could dispense with traffic cops just yet. The lights cycled automatically but an attendant was always on hand to manually override the system and revert to hand signals should a problem occur. If a fire truck approached the officer was instructed to turn all the lights red and wave the vehicle through.

Within a month of the Yonge and Bloor lights going live a bell had been added to the set-up in an attempt to impress on dawdling motorists the urgency of the yellow signal. As you would expect, the overall speed of automobiles was much slower in 1925 - a newspaper report that year described traveling 32 km/h on city streets as "foolish."

The system, despite freeing up traffic police and being easy to understand, wasn't without its detractors. "I have watched motors waiting a full minute where there was no traffic whatever on the cross street. That seems rather absurd," W. G. Robertson, chairman of the Ontario Motor League, a predecessor to the Canadian Automobile Association, remarked after a visit to Atlantic City where signals were widespread.

The group would eventually get behind the idea of traffic lights in Toronto, despite Robertson's concerns about efficiency and cost. At the same time, automobile discussions also touched on whether or not to make twin headlamps and horns mandatory.

Off the back of the successful test at Yonge and Bloor, traffic lights were added at Queen and Yonge, Yonge and Dundas, and 15 other downtown traffic interchanges, this time in a more familiar, vertical configuration on the hydro pole on the opposite corner to the driver. From there, electric traffic lights rapidly proliferated, freeing up large numbers of police officers.

Toronto became the first city in the world to develop and implement a computerized traffic management system in 1963 with the advent of the Gardiner Expressway, Don Valley Parkway, and Allen Road and other surface transportation upgrades.

Fast forward to today and Toronto has over 2,300 sets of traffic signals all centrally-managed out of a high-tech control centre in East York. Every aspect of every intersection is simulated on a computer, optimized based on vehicle behaviour, and regularly tweaked to provide an environment that keep cars moving as best possible.

Still, when the power goes out, Toronto continues to call on its traffic cops.

Please share this

No comments:

Post a Comment