As we've mentioned in previous posts, Toronto is home to some amazing natural features - the Toronto Islands and the mighty Don, Humber and Rouge rivers to name a few - but we haven't touched on the history of the most obvious and influential of them all: Lake Ontario.

Most Torontonians are familiar with the winding Davenport Road and the base of the steep incline it follows, but not everyone knows that the rocky outcrop south of St. Clair marks the former shoreline of Lake Iroquois, a proto-version of Lake Ontario that began to recede at the end of the last ice age leaving behind the Scarborough Bluffs and other notable features of the city.

View Lake Iroquois Shoreline in a larger map

Lake Ontario, to use its current name, has significantly fluctuated in size over the last several thousand years due to the slow retreat of a lobe of the Laurentide Ice Sheet, a massive continent of ice that once covered most of Canada and parts of the United States. The land Toronto is built on today has at various times been under 50 metres of water and stranded well inland.

The utterly vast, sprawling Laurentide - up to two miles thick in parts of northern Quebec - plugged the Saint Lawrence River valley and created giant depressions in the ground. As the ice began to retreat in the face of rising global temperatures, meltwater - channelled by ancient rivers - became trapped in great land basins and formed large lakes, the most easterly of which was Lake Iroquois.

Iroquois was, very roughly, a scaled up version of Lake Ontario. The shape of the shoreline, revealed by various geological surveys, approximately matches that of today's lake only with slightly wider edges and a long extension at its southeast extremity into New York state. This was where Iroquois drained - over the Niagara escarpment and down the Mohawk River - instead of via the Saint Lawrence as it does today.

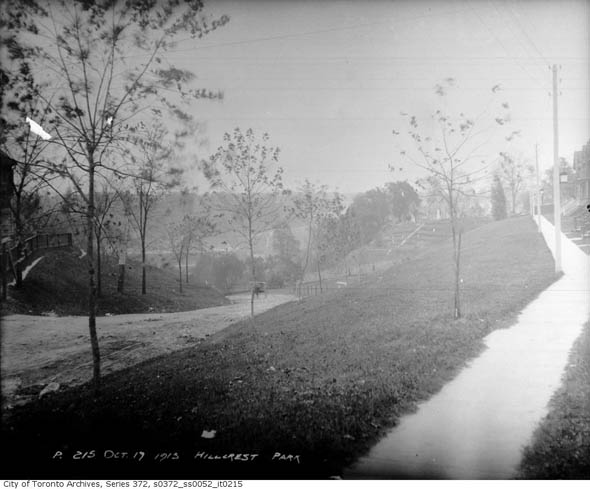

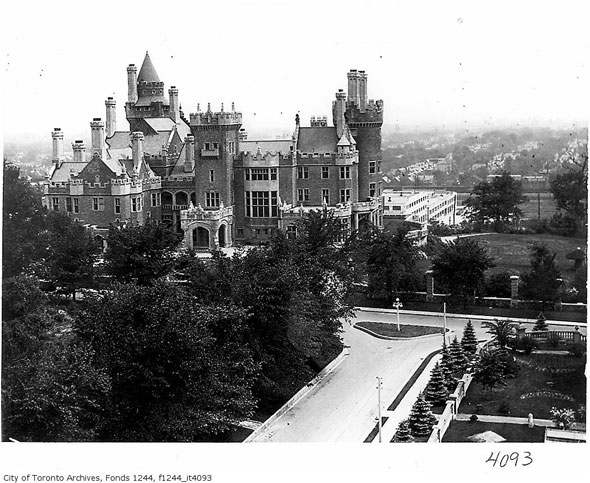

At Toronto, Iroquois' waters lapped the base of the hill north of Davenport Road. Everything south - the entire downtown that is - was once at the bottom of the lake. According to Natural Resources Canada, the water would have been deep enough to half-submerge the Royal York Hotel. Spadina Avenue and Road would later get their corrupted Ojibwa name - ishpadinaa meaning "a high hill or sudden rise in the land" - so called for the escarpment left behind by Iroquois. Casa Loma owes its expansive views to the same feature.

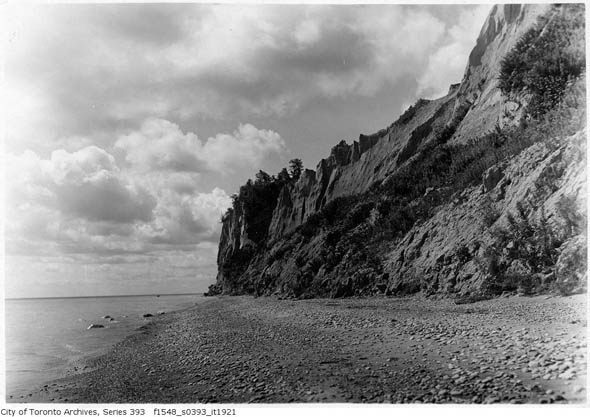

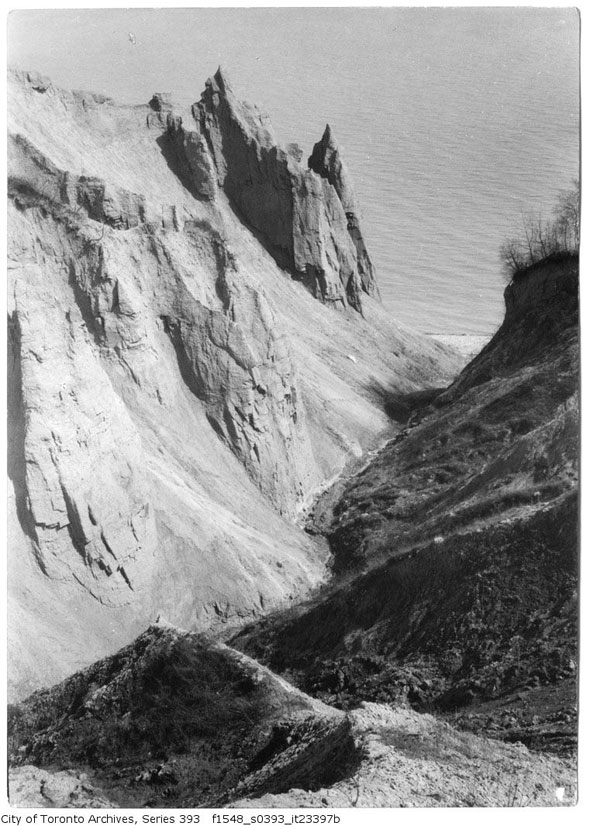

For the most part, the route is relatively easy to follow. Running west to east, the Iroquois shoreline sweeps north from where Dundas Street crosses Etobicoke Creek to the Black Creek underpass at the 401. From this northerly point, Weston Road follows the shoreline back south to Davenport Road, across the city, to an area near Pottery Road. A final inland sweep around East York ends with the Scarborough Bluffs at the shoreline Lake Ontario. The map above roughly illustrates this.

As the Laurentide Ice Sheet retreated north, it left a significant depression in the earth's surface near the northeast corner of Lake Iroquois. As a result, the thawed Saint Lawrence valley began to allow lake water to escape into the Atlantic ocean. Like a small puncture in a swimming pool, the water level slowly but dramatically dropped in the lake, eventually equalizing roughly 20 metres lower than it is today. This new, smaller lake was named Glacial Lake Admiralty and given a separate identity to Iroquois by geologists.

The shoreline of this significantly smaller accumulation of meltwater is still apparent underwater and, according to Wikipedia, is known as the Toronto Scarp to those who know the lake bed.

Slowly, the once depressed land in the northwest that helped drain Lake Iroquois began to rise back in line with the surrounding area, stemming the outward flow of water from Admiralty and causing the water level to rise once again. Lake Ontario is the end product of that final rise.

Winding its way through the city and around the lake, the Iroquois shoreline is a significant geographical feature of Toronto, Ontario and the state of New York, and perhaps our most conspicuous connection to the ancient landscape that existed before the arrival of humans. It might have been punctured and smoothed to allow a gentler incline for several north-south streets, but the escarpment still holds sway over the way we get around Toronto.

Photos: City of Toronto Archives

No comments:

Post a Comment