Lieutenant

Governor of Ontario David Onley is one of four Canadian viceregal

representatives to be (officially) homeless. Toronto pulled down its

last government house, an astonishingly opulent mansion even among its

Rosedale neighbours, in 1959 in the name of cost saving.

Lieutenant

Governor of Ontario David Onley is one of four Canadian viceregal

representatives to be (officially) homeless. Toronto pulled down its

last government house, an astonishingly opulent mansion even among its

Rosedale neighbours, in 1959 in the name of cost saving.98 years ago, on 15 November 1915, the first official guests were welcomed inside the grand hall of Ontario's million-dollar palace. 20 years later it was be derelict. Chorley Park is now largely forgotten, save for the small piece of it that remains on the edge of the Don Valley off Douglas Drive.

Ontario's

first three official government houses were located outside the western

boundary of the town of York, which was then largely clustered around

Front Street, east of Yonge.

Ontario's

first three official government houses were located outside the western

boundary of the town of York, which was then largely clustered around

Front Street, east of Yonge. The first residence, a basic single-floor brick building near Fort York, was destroyed when British troops detonated the grand magazine, a giant weapons cache, while beating a hasty retreat out of town during the War of 1812.

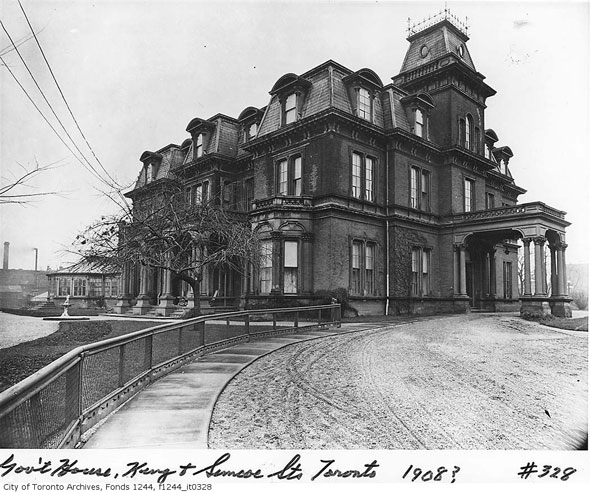

As the city grew, Ontario's viceregal residence found its way to a mansion at the centre of a large plot of land on the southwest corner of King and Simcoe, where Roy Thomson Hall is now.

In the late 1800s, the four corners of that intersection were nicknamed "legislation," "education," "salvation," and "damnation", with Government House representing "legislation." Neighbours Upper Canada College, St. Andrew's Church, and the British Hotel represented the rest.

Elmsley

House, the first of two government houses to occupy the King and Simcoe

corner, stood among lush woodland west of the town. Built in 1798, the

two-storey home would have been a short walk from the centre of

commercial activity and was originally the private home of Chief Justice

John Elmsley.

Elmsley

House, the first of two government houses to occupy the King and Simcoe

corner, stood among lush woodland west of the town. Built in 1798, the

two-storey home would have been a short walk from the centre of

commercial activity and was originally the private home of Chief Justice

John Elmsley.The province bought the building in 1815 and it was occupied by successive lieutenant-governors until 1841. In 1870 a purpose-built government house was built on the former site of Elmsley House and remained there until the arrival of factories and rail lines gave the area a distinctly industrial feel.

The land was sold to Canadian Pacific, which built a rail yard and freight office on the site.

(Interestingly, when the CP building was demolished in the 1970s a mysterious underground room containing a locked safe was revealed. The safe, hauled to the surface by the builders of Roy Thomson Hall, vanished shortly after its discovery.)

With the loss of Old Government House, as it came to be known, the province sought a location for a new residence, one that would outshine of its predecessors in grandeur, a "conspicuous ornament to the city," in the words of William Dendy, author of Lost Toronto.

The province bought a site on Bloor backing on to the Rosedale Ravine - where the Manufacturer's Life Building is now - and held an architectural competition that produced several viable designs. Several were given serious consideration but eventually rejected because of cost.

Fearing the Bloor site would become surrounded by heavy industry like King and Simcoe, the city decided to sell the land and use the proceeds for the purchase of a new location.

Into

the search stepped William James Gage, a wealthy philanthropist and

businessman. He offered to sell his estate at Bathurst and Davenport,

just west of Casa Loma, for the same amount Ontario was willing to pay

for a site in leafy Rosedale. Gage also pledged to use the money he

would earn from the land to establish a public botanical garden nearby.

Into

the search stepped William James Gage, a wealthy philanthropist and

businessman. He offered to sell his estate at Bathurst and Davenport,

just west of Casa Loma, for the same amount Ontario was willing to pay

for a site in leafy Rosedale. Gage also pledged to use the money he

would earn from the land to establish a public botanical garden nearby.The deal appeared to have the support of council and it was suggested the city buy the Rosedale land being eyed by the province, thereby seizing the chance to get two parks for the price of one.

The province, however, had other ideas. It rejected Gage's offer and forged ahead with the Rosedale site, known as Chorley Park, after the town of Chorley in Lancashire, England, the birthplace of Toronto alderman John Hallam.

The final design for the grand residence was drawn up by Francis R. Heakes - the province's official architect also responsible for the Whitney Block on Queen's Park Crescent - in the style of a French Loire Valley château.

Heakes' blueprint borrowed heavily from submissions to the 1911 design competition, including many of the exterior details and the floor plan, and was limited to a budget of $215,000.

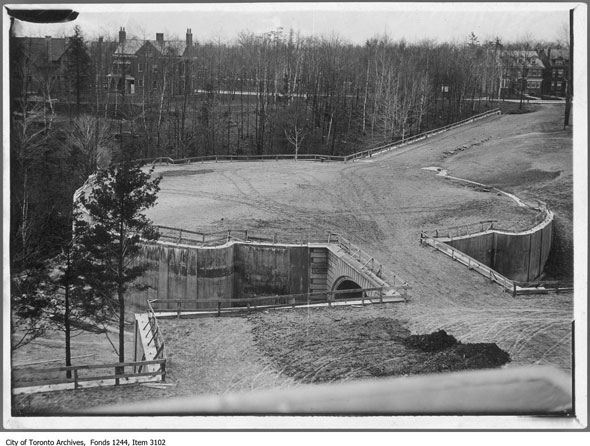

What

rose from the scrubby ground in east Rosedeale between 1911 and 1916

was unlike any other building in Canada. Grey Credit Valley stone

exterior was worked into ornate detail; little tourelles - small

pointy-roofed turrets - embellished the corners of the three-storey

palace - even the chimneys had little architectural flourishes.

What

rose from the scrubby ground in east Rosedeale between 1911 and 1916

was unlike any other building in Canada. Grey Credit Valley stone

exterior was worked into ornate detail; little tourelles - small

pointy-roofed turrets - embellished the corners of the three-storey

palace - even the chimneys had little architectural flourishes.As author William Dendy writes, the château style was in vogue in Canada at the time due to its popularity in France. The railways would build the Château Frontenac, Banff Springs Hotel, Château Laurier, and the Royal York with the same look in the years to come.

Chorley Park's grey stone exterior was capped with red ceramic tile and surrounded by carefully landscaped gardens that included a large square forecourt for receiving official guests. The winding driveway reached the main entrance via arched concrete bridge that still stands today.

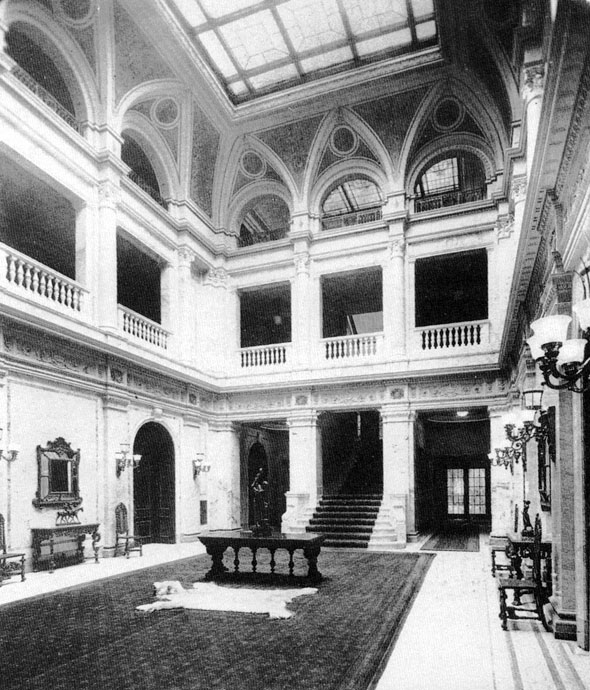

Inside,

an imposing three-storey reception hall basked in sunlught from a

massive rooftop window. Passageways led off to a ballroom with a domed

glass ceiling, the official State Dining Room clad in carved fumed oak

and Caen limestone, a suite of reception rooms, and a glass conservatory

that overlooked the Don Valley.

Inside,

an imposing three-storey reception hall basked in sunlught from a

massive rooftop window. Passageways led off to a ballroom with a domed

glass ceiling, the official State Dining Room clad in carved fumed oak

and Caen limestone, a suite of reception rooms, and a glass conservatory

that overlooked the Don Valley.Much of the interior design work was done by the T. Eaton Company. A photo taken in 1916 shows a full polar bear skin rug with the head still attached at the centre of the reception hall floor.

The bill, when it finally arrived, was more than $1 million - more than four time the original budget. It was deemed worthwhile, however, to secure such a stunning work of architecture. That feeling wouldn't last long.

The

ongoing cost of maintaining the ostentatious mansion proved to be its

eventual undoing. The Conservative provincial government found the cost

even harder to justify as the Depression began to take hold in the

1920s.

The

ongoing cost of maintaining the ostentatious mansion proved to be its

eventual undoing. The Conservative provincial government found the cost

even harder to justify as the Depression began to take hold in the

1920s. Despite voices calling for the house to be abandoned, it lingered on as the official home of Ontario's lieutenant-governor until 1937 when the fine furnishings and fixtures were stripped out and sold at auction.

When world war two began, the gutted interior was converted into a military hospital for wounded soldiers.

Chorley Park met its eventual end in 1959 when, with the last of the patients gone and a brief period as a refuge for Hungarian immigrants fleeing the revolution over, the Metro government under Fred Gardiner ordered the building torn down.

All that remains today is the concrete arch bridge and square forecourt. The land is now a public park, as W. J. Gage once planned.

Ontario's official viceregal residence is currently located in the west wing of the legislature building.

Please share this

No comments:

Post a Comment