It's

tough to picture the tony streets of Yorkville as a pastoral

independent village north of Toronto, but it was once so. Before Hermes,

Gucci, and Prada, Yorkville was populated by Jarvises and Bloores, by

blacksmiths and painters, "cabin'd, cribb'd, and confined within its

narrow limits."

It's

tough to picture the tony streets of Yorkville as a pastoral

independent village north of Toronto, but it was once so. Before Hermes,

Gucci, and Prada, Yorkville was populated by Jarvises and Bloores, by

blacksmiths and painters, "cabin'd, cribb'd, and confined within its

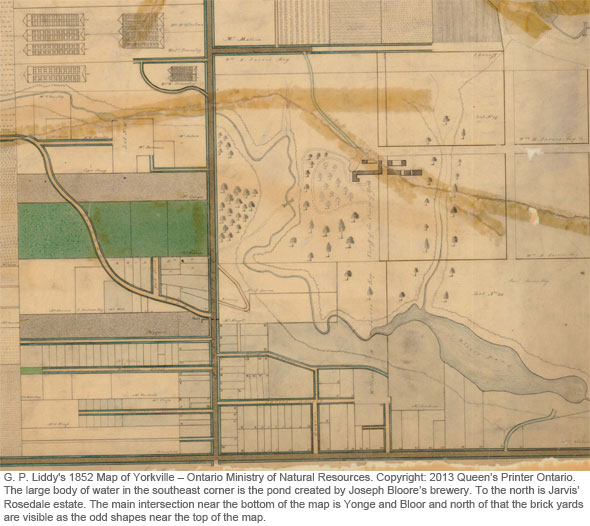

narrow limits."It was here, north of the first concession road, now Bloor Street, that William Jarvis, the owner of the lush 120-acre Rosedale estate, and Joseph Bloore, a brewer with property in the area, would 130 years ago sow the seeds of a new community, the first Toronto commuter suburb and the city's first annexation.

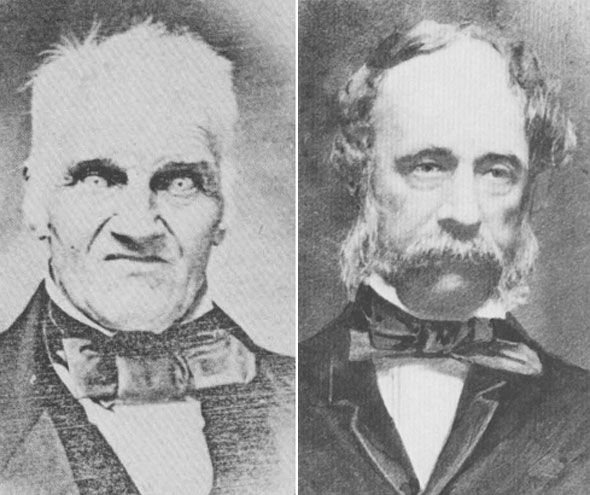

The

most famous image of Yorkville co-founder Joseph Bloore is a difficult

one to forget. Clad in a smart suit and large bow tie, Bloore stares -

positively pierces - with eyes bleached white by an unfortunate

overexposure. His manic, bewildered expression and crop of wild blonde

hair makes him look like a lost cousin of the Addams Family.

The

most famous image of Yorkville co-founder Joseph Bloore is a difficult

one to forget. Clad in a smart suit and large bow tie, Bloore stares -

positively pierces - with eyes bleached white by an unfortunate

overexposure. His manic, bewildered expression and crop of wild blonde

hair makes him look like a lost cousin of the Addams Family.Bloore - now Bloor - was born in Staffordshire, England and arrived in York around 1818. He owned and ran the Farmers' Arms pub near the St. Lawrence Market for more than a decade before switching to alcohol production at a purpose built brewery built a the neck of the Rosedale Ravine.

He dammed the sparkling creek that once flowed along the floor of the valley, forming a large pond popular with skaters, and built a red two-storey brick building with a steep pitched roof and water wheel for processing his product. Just up the north wall of the valley lay the sprawling Rosedale estate of Sheriff William Botsford Jarvis.

Jarvis

was an important member of society in early Toronto. As the elected

sheriff of the Home District, an early sub-region that included York, he

would later temporarily snuff out an uprising against the close-knit

group in charge of Upper Canada, the Family Compact. The Upper Canada

Rebellion culminated in a bloody battle at Montgomery's Tavern just north of Yonge and Eglinton, presently the home of Postal Station K.

Jarvis

was an important member of society in early Toronto. As the elected

sheriff of the Home District, an early sub-region that included York, he

would later temporarily snuff out an uprising against the close-knit

group in charge of Upper Canada, the Family Compact. The Upper Canada

Rebellion culminated in a bloody battle at Montgomery's Tavern just north of Yonge and Eglinton, presently the home of Postal Station K.Jarvis and Bloore both dabbled in land speculation and worked to lay out the earliest parts of the village of Yorkville, just west of Yonge. At the time, the little community would have been no more than few simple homes surrounded by open land. Yonge Street served as the only connection to Toronto and the principle transit route for the horse-drawn carriages of William's Omnibus Line, an early transit provider that ran shuttles from the St. Lawrence Market.

The town was incorporated in 1852 and elected its first council the same year. The inaugural group of leaders consisted of a brewer (John Severn,) a butcher (Peter Hutty,) a carpenter (Thomas Atkinson,) a blacksmith (James Wallis,) and a builder, James Dobson, as reeve. Their professions and initials became the basis of the town's coat of arms, which is still visible on several buildings, including the Yorkville Fire Hall.

In

1858, English builder George Tate was in charge of erecting the town's

parish church. During his time in Canada he helped build the Don Jail at

Gerrard and Broadview and worked to lay the tracks of the Grand Trunk

Railway east to Quebec. In his spare time, Tate liked to collect

watercolours of the streets and houses in Yorkville and Toronto.

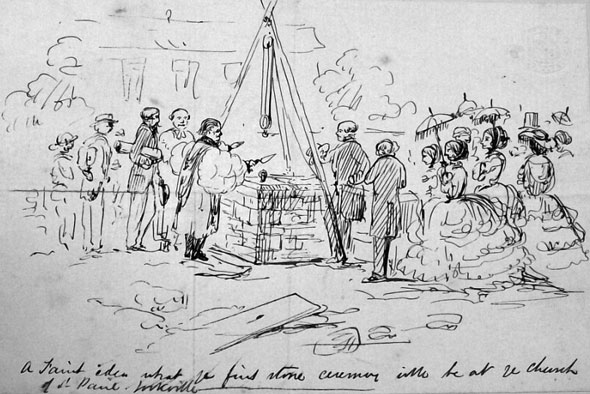

In

1858, English builder George Tate was in charge of erecting the town's

parish church. During his time in Canada he helped build the Don Jail at

Gerrard and Broadview and worked to lay the tracks of the Grand Trunk

Railway east to Quebec. In his spare time, Tate liked to collect

watercolours of the streets and houses in Yorkville and Toronto.His friend and architect Edward Radford sketched domestic interiors and painted scenes typical of the area: men cutting wood, the first golden leaves of fall, speeding horse-drawn carriages, gardeners tending to flowers. His family would later assemble Tate's collection of Radford watercolours and anonymous sketches, possibly his own, into a book that provides a tantalizing glimpse at everyday village life in Yorkville and the images for this post.

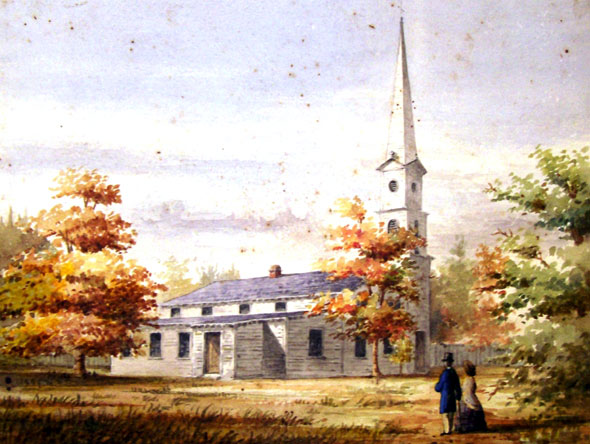

The

white wood frame of St. Paul's Anglican Church, Yorkville's first place

of workship, was hammered together near Yonge and Church on land

donated by Samuel Peters Jarvis, the namesake of the north-south street,

in 1842. Its design was prepared Canada's official surveyor and civil

engineer, John George Howard, one of the major land donors that helped

create High Park.

The

white wood frame of St. Paul's Anglican Church, Yorkville's first place

of workship, was hammered together near Yonge and Church on land

donated by Samuel Peters Jarvis, the namesake of the north-south street,

in 1842. Its design was prepared Canada's official surveyor and civil

engineer, John George Howard, one of the major land donors that helped

create High Park.Despite its simple appearance, raising the 85-foot spire posed a significant engineering challenge for the builders of the day. According to Yorkville In Pictures, a booklet produced by the Toronto Public Library by Stephanie Hutcheson, it consisted of four tree-length pieces of timber turned on end.

Just 18 years later, owing to the rapid growth in the area, the original St. Paul's was at capacity and members of the congregation were forced to stand. A new, larger church was built elsewhere and the first building, barely 20 years old, demolished.

Yorkville

had its own water works, town hall, fire hall, and cemetery, the York

General Burying Ground, more commonly known as Potter's Field, located

on a grassy plain at the northwest corner of Bloor and Yonge. The

non-sectarian burial ground was funded by a group of citizens concerned

about the limited options for non-religious burials in the Toronto area.

Yorkville

had its own water works, town hall, fire hall, and cemetery, the York

General Burying Ground, more commonly known as Potter's Field, located

on a grassy plain at the northwest corner of Bloor and Yonge. The

non-sectarian burial ground was funded by a group of citizens concerned

about the limited options for non-religious burials in the Toronto area.As Jamie Bradburn recalls in history of Potter's Field, Anglican, Methodist, Presbyterian or Roman Catholic faiths were well endowed with places of rest. For anyone not of a religious bent, poor, sick, or otherwise maligned, the options were scant. Many were turned away for fear their interred remains would somehow taint sacred soil.

Potter's Field became a popular burial ground and was at capacity by the late 1840s. The site was closed in 1855 and the remains of 6,685 people were moved to Toronto Necropolis, Mount Pleasant Cemetery, or to other locations arranged by living relatives.

Almost two-thirds of the dead went unclaimed, stalling the sale of the land for more than 20 years. As a result, the uncollected bodies were ultimately fated to be scooped up and mixed together - skulls, ribcages, and all - and reburied in a common grave at Mt. Pleasant Cemetery in 1876.

The

off-white bricks of King Street's St. Lawrence Hall, St. Michael's

Cathedral, St. James Cathedral, and University College all owe their

look to Yorkville's biggest industrial concern, the Yorkville Brick

Yards.

The

off-white bricks of King Street's St. Lawrence Hall, St. Michael's

Cathedral, St. James Cathedral, and University College all owe their

look to Yorkville's biggest industrial concern, the Yorkville Brick

Yards. From a series of pits under today's Ramsden Park, workers chipped at the ancient sand deposits left by the shoreline of ancient Lake Iroquois, a larger version of today's Lake Ontario that once lapped at the base of the hill north of Davenport Road.

Above ground, the clay and gritty soil was pressed into bricks and fired in giant kilns with the factory's other product, ceramic tiles. Clouds of white smoke from the fires can be seen rising over the tree-lined residential streets in pictures of the plant.

Apart

from the brick yards, the Yorkville of the mid-19th century was mostly

quiet and residential. The community was an ideal outpost for people who

preferred to live away from the clamour of Toronto, which at the time

was largely confined to a few blocks directly adjacent to the lakeshore.

Apart

from the brick yards, the Yorkville of the mid-19th century was mostly

quiet and residential. The community was an ideal outpost for people who

preferred to live away from the clamour of Toronto, which at the time

was largely confined to a few blocks directly adjacent to the lakeshore.The people that staffed the village's stores, tended to its gardens, and made its furniture were mostly middle-class and of British descent. In 1870, roughly half the population were born in the British Isles - the rest in Ontario. Stephanie Hutcheson records labourers, painters, blacksmiths, bookbinders, timekeepers, and shoemakers living on Birch Avenue.

They paid low taxes - a point of pride at the town hall - but as a result the vital infrastructure was left lacking. Most of the homes had no plumbing and water was gathered from Yonge Street.

When Toronto annexed the community in 1883 it became officially known as St. Paul's Ward. The takeover heralded an important improvement in services and triggered the town's metamorphosis from rural village, to Victorian residential neighbourhood, to hippy hangout, and finally to Toronto's nexus of glitz, glamor, and sky-high real estate prices.

If they could return for a day, the village's residents would never recognize the place they used to call home.

MORE IMAGES:

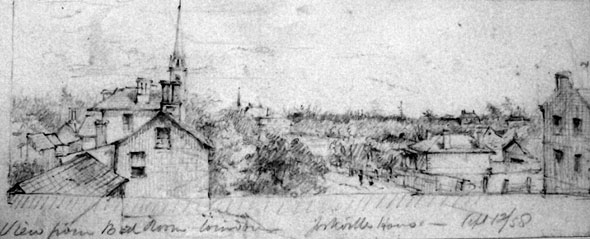

A sketch of the Yorkville skyline in 1858.

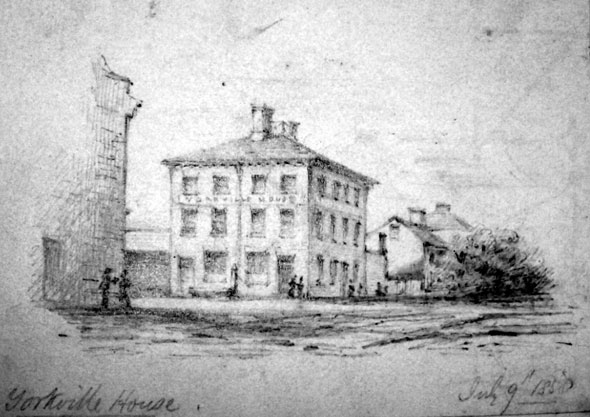

A sketch of the Yorkville skyline in 1858. The exterior of Yorkville House.

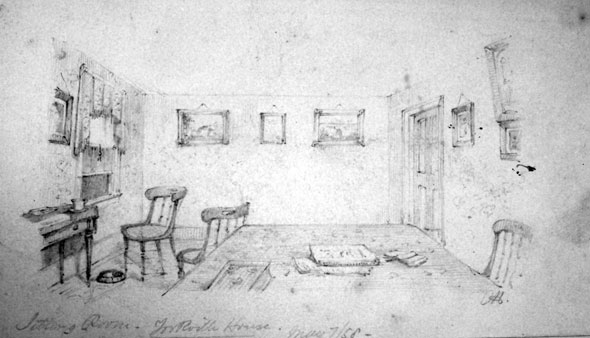

The exterior of Yorkville House. Interior of Yorkville House.

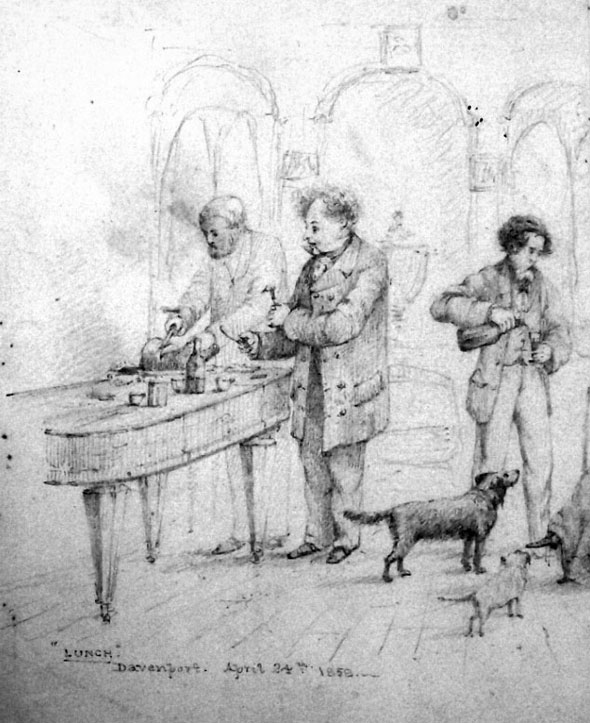

Interior of Yorkville House. A sketch of lunch at Davenport.

A sketch of lunch at Davenport.Please share this

No comments:

Post a Comment