The Militarization of the Constables

When Toronto City Council had finally admitted to the failings of the Toronto Police several years earlier in 1855, it found that one of the principal problems was the ability and experience of the Chief of Police Samuel Sherwood:

The Committee are not aware that any change or want of zeal or activity in the discharge of his duties (so far as he acquainted with it) has ever been established against the Chief of Police but there can be no doubt that he has not that authority over his men or that degree of experience which is absolutely essential to enable him to enforce a proper system of order and discipline.[1]

The

City’s committee on the Circus Riot had recommended in 1855 that

the London Police be approached for a candidate from that force to

take charge in Toronto. But when it came to hire a Chief for

the new force in 1859, Toronto instead chose a military officer and not an experience police officer from the London Police. The new Police Chief was William Stratton Prince, a former Captain of the 71st Highland Light Infantry.

There is a remarkable paucity of biographical detail on Prince and

detail on how his candidacy and appointment unfolded. His

regimental history, however, hints at the qualifications that

Prince brought to the job.

The

City’s committee on the Circus Riot had recommended in 1855 that

the London Police be approached for a candidate from that force to

take charge in Toronto. But when it came to hire a Chief for

the new force in 1859, Toronto instead chose a military officer and not an experience police officer from the London Police. The new Police Chief was William Stratton Prince, a former Captain of the 71st Highland Light Infantry.

There is a remarkable paucity of biographical detail on Prince and

detail on how his candidacy and appointment unfolded. His

regimental history, however, hints at the qualifications that

Prince brought to the job.The 71st Highland Light Infantry was first formed in Glasgow in 1758 and was for the next century one of Britain’s most battle hardened regiments. It fought in America during the War of Independence. The regiment served under Lord Cornwallis in the Carolinas and Virginia, and was included in the surrender at Yorktown, 17th October, 1781; 1782-83 it fought in Southern India; Fought at Conjeveram, Porto Novo, Sholinghur, Vellore, Cuddalore, and Arcot; 1790-1 campaigns against Tippoo Sahib, siege of Pondicherry, Bangalore, Seringapatam; 1805-06 assault landing at the Cape of Good Hope and the battle of Blauberg; 1806-07 assault and capture of Buenos Aires; 1808-09 First Peninsular Campaigns; 1809 Walcharen Expedition; 1810-14 Second Peninsular Campaigns; 1815 at Waterloo took part in breaking the last charge of Napoleon’s Old Guard; Army of Occupation, France 1815-17 : England and Ireland 1818-23 : Canada 1824-30 : Bermuda 1831-33 : Scotland and Ireland 1834-37: Canada, suppressing rebellion and preventing American infiltration attempts 1838-42 : West Indies 1843-46 : England, Scotland and Ireland 1847-52 : Corfu 1853-54.[2]

William Stratton Prince was the son of Colonel John Prince, who commanded the forces engaging the rebels at Windsor in 1838, where he summarily shot rebel prisoners captured there.[3] If Toronto was more concerned about rebellion and disorder than crime fighting, then certainly they had a new Police Chief with rebel-fighting both in his blood and his regimental history. (See more on William Stratton Prince on the next page.)

It appears that upon closer consideration, London was not an appropriate model for the Toronto Board of Police Commissioner’s plans for the Toronto Police. London’s problems and size in 1859 were not comparable to the situation in which Toronto was developing. US police forces were more appropriate to the task, and several were studied, including those in New York, Boston, Albany, and Portland, from which Boston was finally chosen as the best example applicable to Toronto for the systemic regulations of police patrols.[4] The Police Commissioners reported, “Those of the Boston system seems the most applicable to the city of Toronto, and that system has the reputation of being the best and most effective of all the cities in the States.”[5]

The number of constables was fixed at sixty, being “something under one policeman to each 800 inhabitants, which, as compared with populations, is a less number of policement [sic] to a given population than the average number in the cities of the United States to which a reference has been made, while in the city of London, England, there are 6000 policemen in a population of 2 million, being one police man to every 333 inhabitants.”[6] The Commissioners, “found, whenever there is a mixed population and a good deal of intercourse by travel, that one policeman to about eight hundred of the population is thought to be necessary.”[7]

The Board also reported, “In the opinion of the Commissioners no division of labour which provides less than three changes or reliefs in every 24 hours can be accomplished without greatly endangering the efficiency as well as the health and life of the police forces.”[8] Toronto finally had a municipal night watch.

It was decided to dismiss the entire police force: “The Commissioners resolved as a first, and the least invidious step, to dissolve the existing force altogether, and to appoint or re-appoint to the new force such persons only as after a close examination should prove qualified to discharge the police duties, giving the preference in anything like equal qualifications to the members of the old force.”[9]

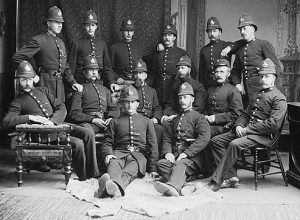

As previously pointed out, only half of the old Toronto Police Force were rehired and most were post-Circus Riot recruits, hired under Toronto’s unilateral board of commissioner “experiment” of 1857-58 prior to the Province’s amendment of the Municipality Act.[10] Fifty-eight constables were actually hired, of which 5 were Presbyterian, 8 Roman Catholic including one of the three Sergeant-Majors, while the remaining 45 were Anglican Episcopalians. At least forty-two constables were Irish, but the nominal and descriptive roll is illegible in portions and a final tally is difficult to determine. (The slightly modified force of the following year shows forty-four Irish constables in a force of 56.)[11] Eight had served in the military, while 19 served on other British police forces, the majority in the Irish Constabulary.[12] The propensity was to hire constable from outside the community of Toronto.

CLICK HERE FOR THE NOMINAL AND DESCRIPTIVE ROLL OF CONSTABLES ON THE TORONTO POLICE FORCE IN 1860

This distancing of Toronto police officers from the inhabitants of the city characterized the new constabulary from the first order issued by the new Chief of Police on February 10, 1859:

Orders

No. 1 Police when on their Beat are on no account to loiter or enter into conversation with passengers in the streets. Should any one address them by asking a question with regards to the locality of any place they will give what information they may have in their power as short as possible, and resume their patrol.[13]

Subsequent orders further delineated the distance Toronto Police officers were to keep from the citizenry:

The men of the Force are given to understand that they are not permitted to lodge at hotels on any account whatever. Constables must have their own private lodgings and on no account be seen lounging and talking about bar rooms and public houses.[14]

It will be the duty of the non-commissioned officer to see that their men reside at the houses of respectable parties. New appointments will also report personally to the Chief the name of the parties they board with and the street and number of the house. The Force are again reminded that residence in saloons and public houses will not be permitted.[15]

The Chief exerted strict control over virtually every aspect of the police officer’s lives. Unmarried officers were housed in special barracks and those wanting to marry, had to get approval from the Chief to do so and for their subsequent place of residence which was restricted to “respectable areas” of the city.[16] Even how officers ate, was a matter of concern for Chief Prince:

The Chief Constable requests the Constables on taking their meals will be respectfully dressed or, he will issue an order to enforce it, he trusts that the majority of the constables out of respect for themselves and what is due to the respectability of the Force, will report to the Chief Constable any constable guilty of an act of gross indecency of this kind, as sitting down with his coat off as conduct of this kind is nothing more or less than a disgrace to the force and will be treated as such.[17]

The constables did not take Chief Prince’s military discipline lightly, even though many had previous military experience. In 1872 Prince introduced ‘beat cards’ which scheduled minute by minute where constables were to be on their beat. The Toronto Police officers threatened to go on strike if Prince and two sergeants did not resign and the ‘beat card’ system was not abandoned. The Board of Commissioners responded by firing the entire force, and when defeated constables began to trickle in requesting their jobs back, sixteen of them were not rehired.[18] In an era when organized labour strikes were rare, it is remarkable to see the Toronto Police among those attempting to take labour action. (The Toronto Police would strike again in 1918.)

Along

with their desirable character traits, Toronto’s constables were

assigned a social class category. The Toronto police officer,

in the estimation of Chief William Prince:

Along

with their desirable character traits, Toronto’s constables were

assigned a social class category. The Toronto police officer,

in the estimation of Chief William Prince:Should be in the prime of manhood, mentally and bodily; shrewd, intelligent and possessed of a good English education; trustworthy, truthful, and of a general good character, in order to command a moral as well as an official influence over those among whom he may be required to act, and subject to the most rigid discipline; he should, in fact, be a man above the class of labourers and equal, if not superior, to the most responsible class of journeymen mechanics.[19]The Toronto Police were thoroughly imbued with military discipline:

The position of “attention” that position which the officers and constables will present at all times in addressing the Bench, and in giving evidence and indeed at all times on being questioned on points of duty, is as follows: The heels must be in a line and closed — the knees straight — the toes turned out so that the feet may form an angle of 60 degrees — the arms hanging straight down for the shoulders — the elbows turned in and close to the sides — the thumb kept close to the forefinger — the Head to be bent and in giving evidence the body, arms and hands to be perfectly steady — in fact — exactly the same position as a soldier in the Ranks or parade addressing his Officer.[20]

Individually Toronto Police officers were expected to perform their duties with moderation in their use of force:

In the arrest of criminals and disorderly characters, drunkards, especially the latter, men are cautioned against the unnecessary use of the baton when persuasion and a little patience on the part of the policeman would suppress all violence on the part of those arrested.[21]

This was strictly enforced when a constable was suspended for giving a prostitute on his beat a kick:

P.C. Taylor was suspended and brought before the commissioners of police to answer to a complaint preferred against him for having wantonly used violence to a woman of bad character in Church Street by giving her a kick. The commissioners find the complaint is correct and caution the said constable to be more careful for the future. Violence is not on any account to be used except in self defense or in prisoners resisting – and it is absurd to a degree that constables should loose all control over their tempers on being abused by a drunken woman. Constables are supposed to be above caring for abuse from persons of that description.[22]

While Toronto Police officers were urged towards moderating the use of force in the performance of their individual duties, they were drilled incessantly in the use of highly lethal collective force. Drill took place three times a week[23] and infantry manuals were distributed to the Sergeant Majors who were expected to drill the constables in battlefield maneuvers.[24] The nature of these drills are vividly outlined in this extract of Chief Prince’s complex orders for the procedure of clearing streets by the use of highly concentrated and coordinated rifle fire:

The following is the order in which street firing is conducted, and in order that men should have a theoretical knowledge of the same as well as practical, the following is a description of the drill with regard to clearing streets.

The company being in column of subdivisions — the commander of the leading subdivision will give the word, “Right (or left) Subdivision” “Ready” “Present” “Shoulder Arms” “Four Deep” and remain steady. The commander of the rear subdivision at the same time giving the following words of command “Rear Subdivision” “Four Deep” “by the left, Quick March.” The subdivision will then advance passing through the opening of fours of the Front subdivision and when advanced 20 paces will halt. The commander of the right subdivision will immediately on the left passing through it, give the word of command, “Front” “Load” then “Shoulder Arms” “by the left, Quick March” whilst the commander of the then leading subdivision immediately on the rear one receiving the word Quick March, will give the word of command, “left Subdivision” “Ready” “present” “Shoulder Arms” “Four deep” — and the right subdivision forming four deep advancing, will proceed through the left halting at 20 paces in front, the rear subdivision at the same time loading as before directed, and thus the subdivisions will advance and fire alternately.[25]

For new reformed Toronto Police in the 1860s, proactive crime fighting was less on the agenda then the preparedness for meeting mass hostile threats emanating from within the city. Where the threat was perceived to come from has already been described above.

Under its next Police Chief, Frank Draper (1874), a lawyer and captain in Toronto’s Queen’s York Rangers Regiment, the Toronto Police would later pride itself in their refinement of infantry tactics for use in urban street fighting, where fewer words of command were needed to deploy the constables:

At least on two occasions the Toronto police were used as a military expeditionary force. In February 1883 when there was a threat to dynamite the Parliament Buildings in Ottawa, the Toronto Police secured Parliament Square and Government House until May. Two years later in October 1884, the Toronto Police traveled by rail to fight illicit liquor gangs who seized the railway line at Michipocoten on the north shore of Lake Superior. [27]The street skirmishing drill, prepared specially also for the Toronto Police Force, is peculiarly a Police drill. The expeditious movement of sections or small detachments in close or extended order from point to point with the fewest possible words of command is the object sought to be attained. A section or any portion of a company can be extended or moved to cover a given point almost instantaneously on a single word of command, and as readily reformed, without any regard to the position occupied by the front or rear ranks. All movements are executed on the double, and have been studied out with a view to a more speedy and effectual suppression or riots and street disturbances.[26]

Nonetheless, despite the constant drilling, Toronto Police never came to use the massive firepower it had available to deploy. Probably the seminal event in Toronto’s Police history, both for its reservation in using mass force and for its relationship to the Irish Catholic populace, is the Procession Rioting of 1875.

As it was noted above, the newly reformed Toronto Police remained predominantly Irish Protestant. The issue of the Orange Order membership in the Police was not immediately resolved. The Police Commissioners originally ruled in 1859 that no member of a secret society might join the force. Pressured publicly by the Orange Order, City Council attempted to overturn the ruling but failed by one vote.[28] The next year when the Tories returned to dominate City Council the vote was taken again and passed, but the Board of Police Commissioners insisted that City Council had no authority to rescind the Board’s regulations, and the order stood and was formally incorporated into the Toronto Police Regulations.[29]

Orange Order Parade proceeding east on King Street (circa 1870)

This photo can be dated by the absence of the spire on St. James Cathedral

visible in the distance. The spire would not be added until 1875, while the camera’s ability to

freeze motion in a short exposure time dates the photo to no earlier than the late 1860s.

While the Irish Catholic population was already singled out as a threat within the city by virtue of their home history, poverty, ethnicity, and unskilled labour status, the Fenian Raids and D’Arcy McGee’s assassination in Ottawa, further cast aspersions on the Irish Catholics and positioned them as targets of police attention. The mostly Protestant Toronto constables were often accused of acting with prejudicial hostility towards Irish Catholics. But in 1875 during huge Catholic processions in Toronto which came under attack by armed Orange mobs, the Toronto Police distinguished themselves not only in their defense of the Catholics, but also for the coolness in the face of the mobs. Despite numerous handgun shots and thrown rocks, the police did not return fire and several constables sustained injuries protecting the Catholic procession.[30] The archdioceses conducted a large cash collection on behalf of the constables in gratitude, and the issue of systemic Toronto Police hostility towards Irish Catholics was put to rest that year.[31] When in 1878, American Fenian O’Donovan Rossa visited Toronto to speak at St. Patrick’s Hall, Toronto Police efficiently and coolly protected him from angry Orange mobs.[32] In the future, the potential military might of the Toronto Police was increasingly directed towards threats from labour unions, as it was against workers during the Street Railway Company Strike in 1886.

While Orange vs. Green clashes in the streets diminished, the Toronto Police were still not about to be deployed as the proactive anti-crime force we associate with municipal policing today.

http://www.russianbooks.org/crime/cph5.htm

Please share this

No comments:

Post a Comment