TORONTO POLICE IN THE 1850s

The Gangs of Toronto and the Call For Reform

Downtown Toronto 1857 — Looking North Up York Street from King to Osgood Hall at Queen Street

The political dynamics of Toronto of the 1850s were radically different from those of the 1830s. The old Family Compact-Tory-Reform issues had faded in the 1840s, despite the occasional flare-ups like the Rebellion Losses Bill riots. Mackenzie, once a fugitive from the hangman, had returned to Toronto and lived out the rest of his life in relatively docile retirement on Bond Street. Change in Toronto began to take a form beyond the context of municipal partisan politics.

Toronto essentially remained a large trading village until 1850. But with British abandonment of colonial trade protection policies and the collapse of the imperial trading route through Montreal and the St. Lawrence, Toronto found itself looking towards the Erie Canal and New York. In 1853 the first railroad in Toronto went into service. By 1856 there were three railways and Toronto was connected to the US networks. The mere existence of the railways lead to a huge manufacturing industry for rails, railway stock and engines, apart from the rise of factories manufacturing goods to put on those trains.[1]

The ethnic balance within Toronto’s mostly British stock was destabilized by the 1850s. The population of Toronto swelled from 23,000 in 1848 to 30,000 by 1850 as a result of mostly Irish Catholic peasant refugees escaping the ongoing famine.[2] The new Irish presence was not warmly welcomed in Toronto. The Reformer George Brown, founding editor of the Globe, did not disguise his contempt for the Irish:

Irish beggars are to be met everywhere, and they are as ignorant and vicious as they are poor. They are lazy, improvident and unthankful; they fill our poorhouses and our prisons, and are as brutish in their superstition as Hindus.[3]

Many arrived in Toronto under the most horrendous circumstances, and Toronto authorities did everything possible that they not remain in the city. Larratt Smith, a rising young city lawyer wrote his relatives back in England about the Irish immigrants in Toronto:

They arrive here to the extent of about 300 to 600 by any steamer. The sick are immediately sent to the hospital which had been given up to them entirely and the healthy are fed and allowed to occupy the Immigrant Sheds for 24 hours; at the expiration of this time, they are obliged to keep moving, their rations are stopped and if they are found begging are imprisoned at once. Means of conveyance are provided by the Corporation to take them off at once to the country, and they are accordingly carried off “willy nilly” some 16 or 20 miles, North, South, East & West and quickly put down, leaving the country to support them by giving them employment…John Gamble advertised for 50 for the Vaughn plank road, and hardly were the placards out, than the Corporation bundled 500 out and set them down…The hospitals contain over 600 and besides the sick and convalescent, we have hundreds of widows and orphans to provide for. [4]

From 1841 to 1848 the percentage of Catholics in Toronto rose from 17 to 25 percent. The new Irish immigrants were a tougher and more volatile people, hardened by the brutal life they experienced in Ireland. They were the source of some of Upper Canada’s first violent labour unrest, rioting on the Welland Canal dig where many were employed at a subsistence wage.[5] Some of the first big mob sectarian clashes in Ontario between the Protestant Orange and Catholic Green unfolded in the Niagara region around the canal construction during the 1840s.[6]

As

Toronto began to gradually nudge its way towards industrialization,

many of the new Irish immigrants began to settle in the city seeking out

unskilled employment. Although these types of statistics are not

available for the early 1850s, those nearing the end of the decade and

early 1860s give us a glimpse of Irish urbanization. According to a

Toronto Catholic Archdiocese census in the early 1860s, forty-five

percent of Toronto’s Catholics were unskilled labourers.[7] The Irish,

both Catholic and Protestant, also represented 67.3 percent of all

arrests in 1858.[8] Irish women, in 1860, corresponded to 84.4 percent

of all female arrests, despite the fact that Irish composed a little

over 25 percent of Toronto’s total population.[9]

As

Toronto began to gradually nudge its way towards industrialization,

many of the new Irish immigrants began to settle in the city seeking out

unskilled employment. Although these types of statistics are not

available for the early 1850s, those nearing the end of the decade and

early 1860s give us a glimpse of Irish urbanization. According to a

Toronto Catholic Archdiocese census in the early 1860s, forty-five

percent of Toronto’s Catholics were unskilled labourers.[7] The Irish,

both Catholic and Protestant, also represented 67.3 percent of all

arrests in 1858.[8] Irish women, in 1860, corresponded to 84.4 percent

of all female arrests, despite the fact that Irish composed a little

over 25 percent of Toronto’s total population.[9]Parallel to this, we begin to see emerging riots and clashes between Orange Protestant and Green Catholic factions increasingly displace the old Reformer vs. Tory brawls. Between 1852 and 1858, six major riots between Protestant and Catholic militants unfolded in Toronto.[10] The city’s Orange-dominated constabulary was of little help in quelling these disorders with any semblance of impartiality.

The 1850s would witness the first union organizing of unskilled workers as well as increasing militancy from skilled trade unions in the face of increasing mechanization and deskilling in manufacturing.[11] In Toronto there were at least fourteen strikes between 1852-1854, a level of labour militancy not to be seen again until the 1870s.[12] The news filtering back to Toronto of riots and revolutions throughout almost all of Europe in 1848, in which monarchies and governments fell, must have made local authorities contemplate the efficiency of the Toronto Police.

The

nature of poverty was also beginning to change. Previously

impoverished peoples were migratory and seasonal.[13] With

industrialization they were now becoming permanently settled in

increasingly densely populated quarters of the city like Macaulaytown in

Toronto’s St. John’s Ward.[14]

The

nature of poverty was also beginning to change. Previously

impoverished peoples were migratory and seasonal.[13] With

industrialization they were now becoming permanently settled in

increasingly densely populated quarters of the city like Macaulaytown in

Toronto’s St. John’s Ward.[14]Not only had the nature of the poor changed, but the nature of the wealthy and those in between as well. The rise of industrial manufacturing in Toronto created not only a new wealthy class, but also a larger property-owning middle-class, eligible to vote. The introduction of omnibuses in the late 1840s, and later street railways in 1860, segregated Toronto into neighborhoods by income and inevitably by class. The perceived threat to Toronto’s middle-class property owners was gradually being shifted from that of spontaneous riots, rebellions, and occasional external incursions, to a more permanent and geographically fixed source from within the city, whose identification gradually began to shift from ethnic to one of class; a focus on the threat from “dangerous classes” of unskilled working poor and destitute unemployed.

Toronto was going to need something more than the type of English parish watch it currently had for a Police Force. The conditions in Toronto during the 1850s began to resemble more those of highly urbanized London, England in the 1830s when the London Metropolitan Police was founded. There was a gradually growing middle-class consensus in Toronto that began to place police reform on a higher priority than Toronto’s political autonomy from the Province. This was clearly being felt in the chambers of the Toronto City Council.

In 1850, City Council debated the viability of establishing a nightwatch no less than five times, but postponed any final decision.[15] There is some evidence, that like in Detroit, downtown businesses in Toronto were beginning to finance their own private nightwatch.[16] City Council debated appointing that watch as special constables and paying them a municipal salary.[17]

The need also to extend the constable’s individual powers was evident as City Council called on:

A law to extend the power of Constable in making arrests of parties guilty of breaking the peace on the authority of persons not magistrates who shall give the constables sureties to appear and prosecute the accused parties before the police magistrates.[18]

The City wanted police magistrates to be granted:

Powers to suppress bawdy houses and to register Gambling Houses.

Power to make byelaws [sic] for the purpose of regulating Boarding houses and for the summary punishment of Tavern and Boarding House proprietors who may be guilty of Fraud or imposition on Immigrants or Travellers.

A Law to punish persons for using grossly insulting language calculated to provoke breaches of the peace.[19]

The nature of these desired measures, indicate that there was a broadly based concern with public order.

Individual identification numbers were issued for the first time to be worn by constables on hats and collars.[20] By 1855, the Toronto Police exceeded fifty constables and by 1857 there would be six sergeants as well, supervising the force across the two divisions into which the city was divided.[21]

Rare view of Toronto looking east along King Street from Yonge Street. Circa. 1860 – US Civil War Era.

Rare view of Toronto looking east along King Street from Yonge Street. Circa. 1860 – US Civil War Era.On the left in the distance one can see the roof of the second St. James Cathedral (1850), which

burned down in 1849 and would not get back its familiar tower and spire until 1874.

Some of the old problems addressed in the 1841 Provincial Commission were still plaguing the Toronto Police. Constables now prohibited from holding liquor licenses, were instead registering them under family member’s or friend’s names.[22]

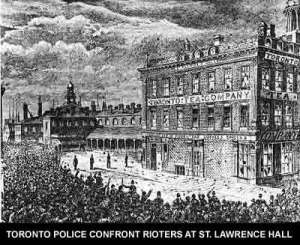

It would be two riots in the summer of 1855 that would expose the Toronto Police to unanimous condemnation in Toronto and illustrate just how far the new industrial middle-class consensus had replaced the old Orange municipal solidarity in the Toronto City Council as far as it came to the Alderman-appointed constables. Ironically, neither of the two riots—the Firemen’s Riot or the Circus Riot, were sectarian in their causes.

Toronto’s Fire department was composed entirely of volunteers, who combined their firefighting activities with social and club activities—sort of like weekend sports teams.[23] On June 29, 1855, a fire broke out on Church Street, and two different firefighting companies responded. Colliding with each other as they attempted to extinguish the fire, it was not long before the competitive firemen dropped their hoses and began to fight. A squad of Toronto constables swooped down to separate the brawling firefighters, who then together turned on the police officers and gave them a thorough beating. In the heat of the moment, the constables ended up charging the firemen with assault.

Toronto Firemen from Firehall No. 11 at Yorkville Avenue (circa 1880)

Like

the police force, most of Toronto’s firefighters, were also members of

the Orange Order. When the matter came to trial, the Toronto constables

had second thoughts about the charges they laid against their fellow

Orangemen, and had to be forced into court to testify against their

fellow-Orangemen. Once on the stand, the constables deliberately

confused their testimony. Reform newspapers the time, practically

howled with indignation. The Globe reported that “it is plainly

asserted by those who have access to the best information that during

the days which have been allowed to elapse since the fire, a compromise

has been effected between the constables and the firemen, who are too

much birds of a feather long to differ.”[24] The Examiner denounced

the event as “Utterly disgraceful to the administration of civic

justice, this case demands the reconstruction of the police force which

thus proves itself utterly corrupt.”[25]

Like

the police force, most of Toronto’s firefighters, were also members of

the Orange Order. When the matter came to trial, the Toronto constables

had second thoughts about the charges they laid against their fellow

Orangemen, and had to be forced into court to testify against their

fellow-Orangemen. Once on the stand, the constables deliberately

confused their testimony. Reform newspapers the time, practically

howled with indignation. The Globe reported that “it is plainly

asserted by those who have access to the best information that during

the days which have been allowed to elapse since the fire, a compromise

has been effected between the constables and the firemen, who are too

much birds of a feather long to differ.”[24] The Examiner denounced

the event as “Utterly disgraceful to the administration of civic

justice, this case demands the reconstruction of the police force which

thus proves itself utterly corrupt.”[25]Few weeks later on July 13, 1855 both the firemen and police officers, were implicated together in the Toronto Circus Riot. A circus came to town from the USA. That night, clowns from the circus visited a King Street bordello and got into a brawl with some local citizens. The clowns got the upper hand, seriously injuring two Toronto patrons, who were also members of the Hook and Ladder Firefighting Company. The next day, a crowd of rowdy locals gathered at the circus, and attempted to pull the tent down. At first the circus people held off the crowd but soon the Hook and Ladder Company arrived, and with their company wagon, pulled the tent down and the circus was overrun. The clowns escaped, but circus wagons were overturned and set fire to by the firemen. The Toronto police in the meantime stood by and watched without interfering. Only when the Mayor called the army out, was the rioting halted. Again, the Toronto Police came under severe criticism when 17 of the rioters were arraigned in court but not one constable could remember seeing the accused at the scene. The Globe complained, “There are three classes in the city which thoroughly understand one another as hale fellows well met—the innkeeper, the firemen, and the police. These classes are fed by the Orange Lodges.”[26]

Corner of King and Yonge Streets (1868)

Corner of King and Yonge Streets (1868)On the 17th of March 1858, there was rioting again between Orange and Green factions on the occasion of a St. Patrick’s procession resulting in a stabbing death. This time it was Chief of Police Samuel Sherwood who refused to testify against a fellow Orangeman implicated in the violence.[27] Chief Sherwood further deepened the dissatisfaction with Toronto’s police system when in the October of 1858 he unilaterally released a prisoner accused of bank robbery. Mayor Boulton demanded the resignation of the Chief but City Council refused to support it. Boulton resigned in protest in November.[28]

In the next election, a Reform candidate, Adam Wilson was elected—the first Reformer to be chosen to the Mayor’s office in two decades. In the previous year, George Brown was elected to the Provincial assembly on a Reform ticket as well. The legislative climate was right for the enactment of police reform in Toronto and in 1858, the legislature of Upper Canada enacted the Municipal Institutions of Upper Canada Act, Section 374 of which provided that in each of the five cities in the colony there was to be a Board of Commissioners of Police. Section 379 provided that “The Constables shall obey all the lawful directions, and be subject to the government of the Board…”[29] This section was gradually expanded to include other municipalities in the province and is still today the effective regulatory system for municipal police departments in Ontario.

Historians have broadly painted the enactment of the Municipal Institutions Act as an imposition of a Police Board regulatory system by the Province upon a corrupt Toronto City Council attempting to cling to its power over the city’s police.[30] City Council minutes tell a different story.

In the wake of the Circus Riots a committee of Toronto Aldermen reviewed the conduct of the police. In the twenty previous years of collective misbehavior by Toronto’s constabulary, City Council rarely censured the police constables its Aldermen had nominated and appointed to the force. By 1855 the attitude was much different:

The Committee of Council having carefully considered the whole of the evidence brought before them relating to the conduct of the Police Force at the late disgraceful riot on the Fair Green on the night of the 13th instant are unanimously of opinion:

That the Force did not act on that occasion in a prompt and energetic manner, which might have been expected from any well regulated constabulary but on the contrary displayed an utter [lack] of efficiency and discipline.

The committee are further of opinion that an entire change should at once be made in the organization of the Force…

It must be evident to everyone who had had an opportunity of perusing the evidence that there is at present an entire absence of any system of organization or discipline in the Police…

The committee are decidedly of opinion that the present mode of appointing the Police is highly objectionable and that the power of appointment ought not to continue to be vested in an elective body like the Council.

First, because it is necessarily more or less liable to this abuse that private or political considerations may have more weight in the appointment of the men than their individual fitness for the Office.

Secondly, Because it is hardly possible that any committee of the Council can or will make that vigorous investigation into the previous character and the physical or moral qualifications of the various applicants, which could and would be made by parties independent of popular control and who would be held personally responsible for their choice.

The Committee also most strongly recommend that for the future the power of appointing and dismissing the members of the Police Force should be vested absolutely in the Police Magistrate, the Recorder and the Chief of Police.[31]

In the meantime, the Province in 1856 began to consider legislation for a province-wide police force of 350 constables to be controlled by government-appointed police commissioner and two-thirds paid for by the municipalities to replace the local constabularies.[32] Mackenzie’s Weekly Message warned that the bill was a “new dodge of a Roman Catholic Police from Lower Canada to take the place of our Protestant police.”[33] The bill was abandoned, however, in May after a ministerial crisis and the resignation of Premier Allen MacNab.

City Council in the meanwhile had petitioned at the same time the Provincial Assembly to instead, “Amend the Municipal law (12 Vic Chapter 81 Sec 47) so as to place the appointment and dismissal of all the Police Force of Cities except the Chief Constable in a Board to be composed of the Mayor, Recorder and Police Magistrate.”[34]

The Province finally enacted the necessary amendments in 1858, while Toronto City Council unilaterally made several different attempts at forming a Board of Police Commissioners on its own starting in 1857.[35]

In December 1858, the Provincially sanctioned Toronto Board of Commissioners sat down for the first time and began to make plans as to how to replace the constabulary with a new police force. On February 8, 1859 the entire force from the Chief down to constable was dismissed and a new one took its place the next day. Only twenty-four of the old constables would be rehired on the new force of fifty-one men and seven NCO’s.[36] Toronto’s current police department today traces its regulatory and institutional lineage directly to the 1859 department and regulatory structure governing it.

http://www.russianbooks.org/crime/cph4.htm

Please share this

No comments:

Post a Comment